Spiritual Sites of Temagami

Trying to keep up with the giant man was magic enough for a six-year-old. Charlie was an elder from the Curve Lake Reserve north of Peterborough—a master woodsman who had been hired by my father to work on a survival movie he was filming for the Department of Lands and Forests. When they weren’t filming, Charlie would take my brother and I into the bush and teach us magic—like boiling water in a birchbark pot. This day my father tagged along because Charlie was taking us to see the carvings in the rock—the Stoney Lake petroglyphs, a secret place connected to the gravel road by an overgrown trail. Only Charlie knew the trail.

Charlie seemed to float through the shadows along the rough trail on a cushion of air while the rest of us tripped and struggled and swatted at mosquitoes. An opening suddenly appeared, the sun illuminating a sloped terrace of rock surrounded by lush juniper and a picture book full of what looked to me like cartoon characters chiseled into the granite. Charlie told us not to walk on the rock. We didn’t. He explained what the characters meant, but I didn’t understand what he was saying. He just smiled, said something in a strange language, then took tobacco out of a pouch he carried and scattered it over the rocks. It was 1957.

Years later I would still remember my first trip to a First Nation’s spiritual or “teaching” site and attempt to put everything I thought I knew about the wilderness, about the natural world, about our Indigenous people, in a better perspective. My apprenticeship to all things wild took decades of peeling off the colonial layers I was born with, to understand what I didn’t understand and to humble myself to some greater power. Travels and experiences, conversations with Indigenous folk, study, research: all brought clarity, but not answers to all my questions. Some questions remain with me still, always will; part of the Great Mystery perhaps, but in the least I have been gifted with just a little bit of insight of which I am eternally grateful.

There are myriad spiritual or religious sites located across the Canadian Shield of Ontario. I have experienced most of them: Thunderhouse, Fairy Point, Agawa Rock—all reside along the Missinaibi River, from Lake Superior to James Bay—the Artery Lake pictographs on the Manitoba border within Woodland Caribou Provincial Park; Lac Lacroix burial mounds and, of course the Stoney Lake petroglyphs. This names only a few. Interestingly, there have been more than a dozen deaths at these sites; and with these tragedies there were numerous stories related to strange happenings.

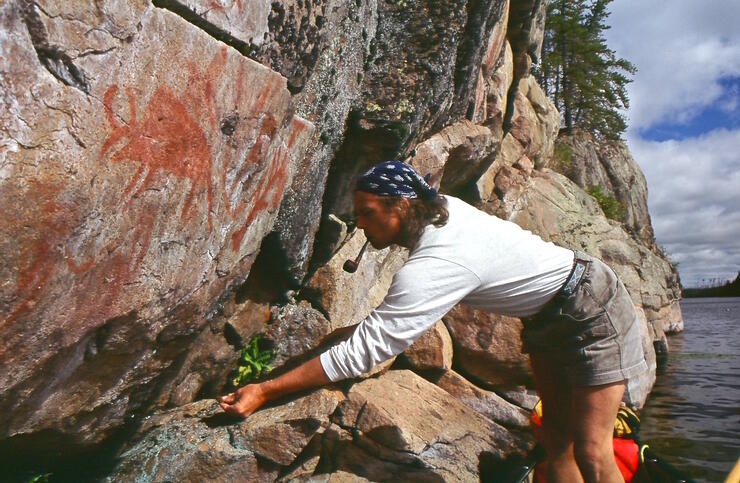

Dennis Smyk, archaeologist from Ignace, Ontario, has documented over 600 habitation and pictograph sites, and of visitors he says, “…most are unable or unwilling to interpret or acknowledge beliefs associated with the paintings.” Because of the simplistic style in which they are presented, rock paintings are often christened as graffiti art when in fact, the artist/shaman, or teacher, presented them as a message, an historical account or teaching. Spiritual teaching sites were carefully chosen for geographical location, associated environment, and rock type, but also for its spiritual pith or energy. Known as places of harmonic conversion, spiritual sites offered a portal between the corporeal and incorporeal worlds. Leaving offerings such as medicine bundles or tobacco was mandatory in order to show respect and to appease residing spirits. To disregard this practice, a show of impertinence could often times solicit trouble.

TEMAGAMI

Temagami is unique in many ways: iconic hallmark features include some of the last stands of old-growth pine; the magnificent hills of the rock-knob upland, the world’s oldest rock; a species of fish—the aurora trout—found only in the high-country lakes of the Lady-Evelyn Smoothwater Wilderness Park; the world’s oldest boys' canoe camp and associated paddling routes that web-work through a glorious melange of inter-connected lakes and rivers. But most importantly, Temagami is home to one of the world’s still intact Indigenous trail systems… namely, the Nastawgan. Connected to these world-class canoe routes are several outstanding spiritual sites, many still used as places of healing and meditation. They all reside in n’Daki-Menan, or “our land”… the traditional lands of the Teme-Augama Anishnabe.

Maple Mountain – Chee-bay-jing, “the place where the soul spirit goes after the body dies”

The mountain is one of Ontario’s loftiest peaks, rising over 1,000 feet above the surrounding lakes. Although ranking thirteenth highest in elevation above sea level, its impressive vertical height above the surrounding landscape makes it the loftiest of Ontario’s 25 “mountains.” It is easily accessed by canoe and remains one of the most popular hiking destinations in northeast Ontario. It was once tribal custom to lay bodies at the foot of the mountain; the challenging hike to its summit is still used by the TMA as a place of meditation and vision-seeking. On the stranger side of things, 10 people have perished on the mountain over the years. The sacredness of Maple Mountain has been ignored on several occasions, through development schemes, logging threats, fire tower and radio installations, and even graffiti on the rock walls. (To read more, see the chapter on Maple Mountain in Trails and Tribulations by Hap Wilson.)

Ishpatina Mountain – Ishpadina or Ishpudina, “the high hill or mountain”

I remember back to the late 1970s, working as a park ranger in Temagami, where one of my prime objectives was to revive the old ranger trails to the summits of all the high places in Temagami. Once active fire-tower locations, the trails had not been cleared for years; it was likely that the original trails were used by Anishnabe vision-seekers.

Ishpatina is the highest mountain in Ontario at 2,295 feet above sea level. This “serpent-mound” flanks the western edge of n’Daki Menan, north to the fine sand beaches of Smoothwater Lake—a spiritual place as noted by anthropologist F.G. Speck (Family Hunting Territories and Social Life of Various Algonkian Bands of the Ottawa Valley, Canada Geological Survey 1915). The canyon north of the high point is deeper than that of Oiumet in NW Ontario; it is also the west starting point of an ancient bon-ka-naw, or winter trail that follows a natural fault line more than 100 km to the Ottawa River valley (Craig McDonald’s Indigenous Map of Temagami).

Spirit Rock – Chee-skon-abikong sakaigan, “place of the huge rock lake”

In 1972-3, I wintered on Diamond Lake when I was 21, and on my way south to pick up supplies at Bear Island was caught in a blizzard at Spirit Rock. When the snow stopped and I could see the cliffs and the 75-foot “conjuring” stone, I knew that this had to be a special place. The surrounding old-growth pine forests became the iconic environmental symbol by the protectionist group Temagami Wilderness Society in the late 1980s. The “Wakimika Triangle,” now protected as a conservation reserve, with its network of hiking trails and scenic beauty, attracts a growing number of paddlers each season.

Anishnabe linguistic expert and historian, Craig Macdonald, says of Chee-skon: “The name is derived from the root word for ‘shaking tent’—the seven-poled, open-topped shelter used by medicine healers (shamans).” Chee-skon was, and still is, a place of powerful divination. Small, bowl-sized depressions surrounding the base of the 30-metre column of rock are naturally filled with water; people seeking visions or healing sat at these pools and stared into the future in a trance-like state.

Anishnabe elder Alex Mathias “Jusquado,” living off the Bear Island reserve on his own homestead and traditional family lands, acts as steward of spirit rock and hosts the annual “changing of the seasons” ceremony. Of the ancient pine of spirit rock, past chief of the TMA, Gary Potts, claimed that “by touching an old pine tree I can connect with my ancestors,” denoting the cultural and spiritual importance of Temagami’s ancient forests.

Just to the south of Spirit Rock, on the east shore of Obabika Lake are Ko-ko-mis and Sho-miss, grandmother and grandfather rock—an impressive twin-rock outcrop and an important spiritual site where medicine bundles are still left in appreciation and reverence.

Wolf Lake – ma-heen-gun sakaigan

Few places in Temagami can compare with the resident beauty of Wolf Lake with its red pine forests, aquamarine waters and impressive cliffs and hills. Ma-heen-gun pu-kwud-in-ong, or “at the place of Wolf Lake Hill,” the notable hill at the southeast corner of the lake, rising a striking 500 feet, was likely a popular vision-quest site for regional Anishnabe. Wolf Lake has been the subject of political and environmental concerns over mining and protection status (earthroots.org).

EXPLORE WITH THE UTMOST RESPECT

I’ve only touched on the number of important spiritual sites in the Temagami region; there are dozens of pictographs, dolmaen-stones, petroglyphs and petroforms, most whose locations should remain known only to the Teme-Augama Anishnabe. Other places of importance include Florence Lake and Smoothwater Lake where archaeology and pre-history date back 5,000 years; “Devil Rock”—the 300-foot cliff overlooking Lake Temiskaming, home to the may-may-gwish-i-wok, or “stone-people,” now used as a popular place for climbers.

It is imperative to treat these places with the utmost respect. Spiritual sites of the Ontario Canadian Shield are a valuable part of our national heritage and continue to serve the Indigenous people in ways we often misinterpret or don’t fully understand. And as archaeologist Dennis Smyk suggests, “minds can be changed…”—referring to our ability to appreciate a part of the natural world we often take for granted.

Local Outfitters

Recommended Articles

March Break in Ontario

Crown Land Camping

2026 Triathalons

Insider’s Guide to Sleeping Giant

Backpacking Trails in Ontario

Natural Highs

9 of the Most Beautiful Fall Destinations

Best Places to Glamp in Ontario

Go Foraging in Ontario

Best Small Towns in Ontario

Where to See Ontario's Coolest Wildlife

Beach Camping in Ontario

Backcountry Skiing in Ontario

WANT A PERFECT CANOEING COMPANION?

Best Backcountry Camping in Ontario

Best Cross Country Ski Spots

Rise and Glide

Best Stargazing in Ontario

Dogs Welcome!