Mapping The Canadian Canoe Trail

Okay, here’s the thing: I said I would never do another canoeing guidebook. Why? Because it means long periods of solo paddling away from my family, insufficient funds spread out over an average of four years of field and studio work, hours—no, days, weeks really—of intense research, and the hand-drawn maps! No wonder all the contemporary cartographers are going digital—who in their right mind would sit for months hand-drawing paddling maps?!

And yet, when Trans-Canada Trail people approached me in 2009 with the notion of “constructing” a water trail from Thunder Bay to Manitoba, how could I refuse such a proposition? After all, the canoe route was Canada’s first trail, historically, but more importantly—prehistorically! The Canadian Canoe Culture and the portage routes were, and still are, an integral part of the heritage that defines this country. The onigum of Northwest Ontario and the nastawgan of Northeast Ontario (traditional First Nations words for portage trail), together make up the largest intact indigenous trail system in the world. That is something to be very proud of.

So, the Great Trail, formerly the Trans-Canada Trail, hit an impasse when they reached the west shore of Lake Superior. The same problem that faced railroad builders a century and a half ago now resurfaced to impose impossible demands on TCT budgets, not to mention the technical problems of building a land-base trail across the morass of lakes, swamps, rivers, and canyons of Northwest Ontario. A water trail that defined the Canadian Canoe Culture was a brilliant idea… really, the only other option the TCT bureaucrats had. Sure, the Mackenzie River had already fixed the gap north to the arctic veldt, but the quintessential portage trail was still missing—a paddling adventure that would whet the appetite of any canoeist, kayaker, or SUP’er.

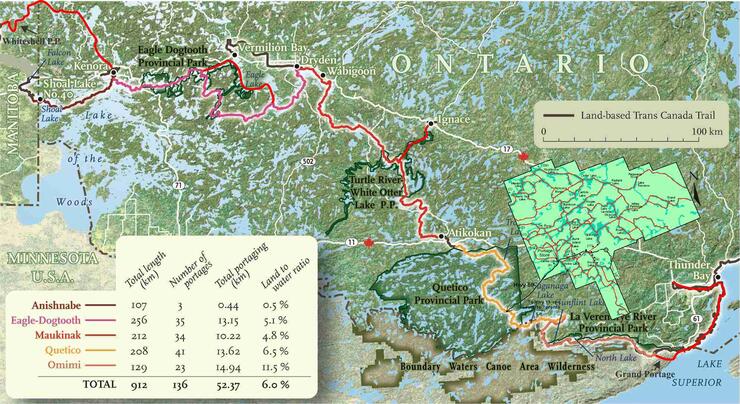

“It’s only 500 kilometres,” Dan Andrews of the Ontario component of the Trans-Canada Trail told me. “As the crow would fly,” I replied, doubting the contrived distance. No canoe route will be in a straight-line configuration, I mused. It wasn’t. And after four years of field mapping, the route was more than 1,100 km! That’s five percent of the total coast to coast to coast trail.

We could have easily taken the easy route along the entire Voyageur route, following the International border to Lake of the Woods, then northwest along the Winnipeg River to Manitoba. The criteria, though, molded a more circuitous route in order to connect all the major communities. Not an easy task when trying to knit together a route that makes sense. The Trans Canada “Great Trail” also needed to exhibit all those unique features that delineate an exceptional experience.

With the help of local canoe gurus Jeremy Brown of Kenora and Garth Gillis of Dryden, I managed to chart out one of the most interesting and diverse canoe trails in Canada. Sitting in the bar at Dryden’s Riverview Inn, scoffing back a beer, and eating homemade ice cream (the concoction of all great ideas), Garth exclaimed, “Let’s call the canoe trail the Path of the Paddle, in honour of Bill Mason.” It was a brilliant notion. Paddling icon and “father” of the Canadian Canoe Culture, Bill Mason brought canoeing alive through his series of films and books entitled Path of the Paddle. Bill also hailed from Winnipeg and knew well the waters around Whiteshell Park at the western terminus of the proposed route, and was a stellar camper at Shoal Lake’s Pioneer Camp. With permission from the Mason family, the Canadian Canoe Trail now had a very fitting appellation.

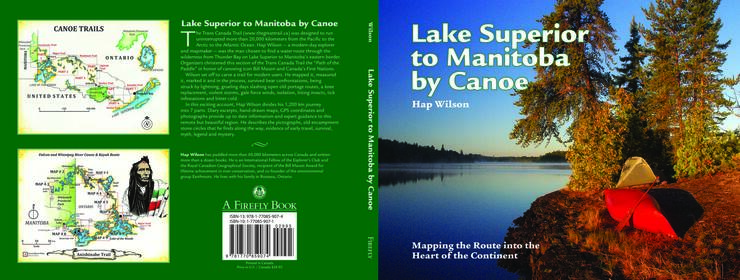

The Path of the Paddle is broken down into seven distinct sections, each with a starting and end designation and particular features that make them unique. Even though a paddler can accomplish this canoe trail as a contiguous route, in either direction, the best way is to approach each section as an independent adventure, taking advantage of water flow and wind direction. And yes, there is a guidebook to help you through all this, published in 2017 by Firefly Books. But wait! There is a lot more to this story.

Sure, the canoeing guidebook is an assist to the adventuring paddler, but there is a more salient expression within the folds of this manual. Canadian history, for one—I didn’t sugar-coat it, nor did I pull any punches when it came to environmental propriety or First Nations accounts of white-man colonialism, greed, and bad deals. It’s all there, in what may well be my last canoeing guidebook. It is the stuff that defines us as Canadians: sometimes raw, sometimes an embarrassing truth, but undeniably a linear route through spectacular Ontario Shield country.

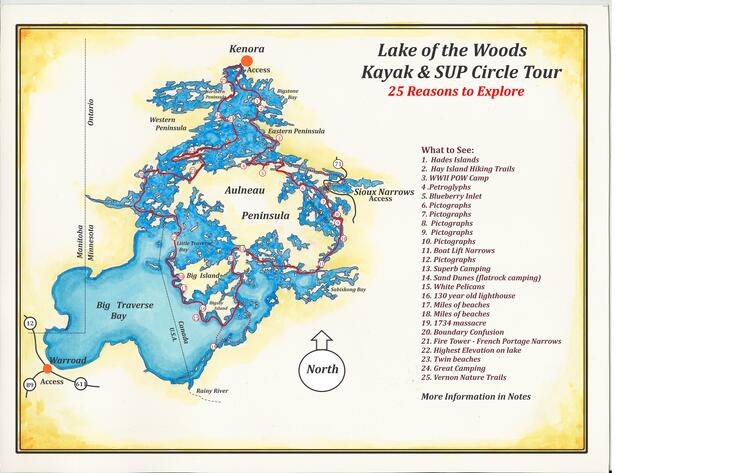

The Path of the Paddle Canadian canoe trail is not just for the adventuring canoeist; some of the country’s best kayak and SUP (stand-up paddleboard) water can be found along the Superior coast southwest of Thunder Bay. Lake of the Woods with its thousands of kilometres of undeveloped shoreline, Indigenous prehistory, and unique flora and fauna could keep today’s paddler mesmerized for decades.

Another added adventure component is the number of backcountry trails scoped out along the entire route; established trails to waterfalls, scenic overviews, even a path to a curious magnetic rock.

The Omimi Trail (shown above) follows the historic Voyageur Route, a heritage river along the Pigeon/Gunflint system that offers impressive hiking within the Superior National Forest.

Don’t expect armed security forces along the American border; surprisingly, the International boundary is totally undeveloped and you’ll find yourself portaging back and forth from Canada to the United States. For those die-hards in need of a good work out, there is the 14-km Grand Portage at the Superior end of the route.

The Path of the Paddle unveils old mine excavations, WWII prisoner of war camps, Jimmy McOuat’s ghost wandering around his impressive four-story log castle on White Otter Lake, billion-year-old mountains worn down into flat-topped diabase mesas, thousand-year-old Indigenous rock paintings, prickly pear cactus! There are more than a dozen rivers, from quaint, passive float-trips to the magnificence of the historic Winnipeg River, and... just enough whitewater to pacify the adrenaline junkie.

Time, natural forces, and industrial intrusion have all played a dramatic role in affecting the decorum of the ancient canoe trail. Part of my job was to bind together a route that avoided modern disturbances. Not always an easy task.

Many of the portage links had long disappeared and, in some cases, did not exist at all. Armed with a trail axe, bush saw, and a pair of loppers; aided by my kids (Alexa and Chris) and my wife Andrea, we were able to clear old portages and build new campsites where required. Although it was oftentimes arduous labour, having my family join me (along with our collie Oban), the task of opening old routes became a labour of love… sort of.

But there were times when mapping the route pushed the limits of the season, from early break-up in May to the freezing temperatures of late October, even treks in winter by snowshoe—all part of the exploration process, to get the four-season feel of the environment, people, and history. Bear confrontations, micro-burst tornadoes, tick infestations, biting flies, and isolation are all a part of the mapping progression—not a negative factor, but a realization that you are a subjugate to the whims of nature. In a beautiful world that affords such exemplary canoe explorations, peace, and connection, there really are no negative influences.

After seven years working on this guidebook, I can honestly convince myself that this project was an honour for me. To be able to help construct the quintessential Canadian Canoe Trail, spend the time out there, and perhaps bring to light some of the pending issues, and to highlight the extraordinary uniqueness of our northwest provincial canoe culture.

Resources:

Lake Superior to Manitoba by Canoe: Mapping the Route into the Heart of the Continent by Hap Wilson; Firefly Books ISBN-13:978-1-77085-907-4

Recommended Articles

French River Canoe Tripping

Dog-Friendly Canoe Tripping Destinations

Algonquin Park Canoe Trip Guide

Backcountry Beginners

The Spanish River

Escape the Crowds

Temagami Canoe Trip Routes

Quetico’s Best Canoe Routes

So Many Places to Paddle

Best Canoe Maps in Ontario

Find Wilderness South of Algonquin

Temagami Canoe Trip Guide

The Massasauga Provincial Park Guide

Ontario’s Blue-Water Lakes

Missinaibi River Canoe Trip

Ontario’s Moose Hotspots

Best Sites on the French River

Do you want to take this pic?

10 Best All-Inclusive Canoe Trips