A Beginner's Guide to Rock Climbing in Ontario

So, you want to climb rocks. We don’t blame you. A day of rock climbing is a day of fresh air, great exercise, outdoor exploration, exhilarating views, personal challenge and, above all, adventure.

The barriers to entry might seem significant at first. You are, after all, climbing a cliff. But a little knowledge will go a long way toward getting you out on the rocks. The best news is that rock climbers tend to be a welcoming lot. Read on below to find out how you can become one with the chalky-hand crowd.

GYMS

The easiest way to get a taste of rock climbing is to visit an indoor gym. Staff will rent you gear, familiarize you with the equipment, and present you with dozens of routes tailored to different ability levels. Find a list of 30 indoor climbing gyms in Ontario here. They are a great place to get your finger tendons strengthened and to find your new climbing friends

Of course, indoor climbing isn’t really climbing on rocks. It’s climbing on plywood and smooth stucco. Think of gyms as your stepping stones to getting outside. To that end, look into gym-organized outdoor days to local crags, like those offered by ARC climbing gym in Sudbury and Boulder Bear Climbing Centre in Thunder Bay.

COURSES

Starting in a gym isn’t mandatory. All across the province, there are operators ready to take beginner climbers out onto rock for the first time. The Alpine Club of Canada has sections in Toronto, Ottawa, and Thunder Bay that organize courses. Or look for commercial operations. Companies that operate along the Niagara Escarpment include Zen Climbing, On the Rocks Climbing, and One Axe Pursuits. For the Haliburton area, check out Elements Guiding; for Sault Ste. Marie, look into Superior Exploration; in Thunder Bay, contact Outdoor Skills and Thrills and Boulder Bear Climbing Centre. Outdoor Skills and Thrills owner Aric Fishman knows that knowledge is better entrenched when it’s repeated. He often offers free refresher outings for previous students who want to follow up.

GUIDES

If you’ve already done the course thing, or consider yourself beyond instruction and just want to get on the rocks with some supervision, many of the same operators that offer courses will set you up with a guide for the day. Check out the guiding operators at all the operators listed for course offerings above (except One Axe Pursuits). If you are in Northwest Ontario, Green Adventures will show you around the steep mineral wealth around Kenora.

GEAR UP

Being a self-supporting rock climber requires a fair amount of gear, but when you are getting into the sport and climbing indoors and with climbing school or guides, you probably only need a harness, shoes, and the all-important chalk bag (used for fiddling with while trying to work out the crux of a route). If your shoes are comfortable, they are too big. They shouldn’t be painful, but any extra space around your toes will compromise your ability to stick that micro-toe hold. To stock up on climbing and related gear, check out Ramakko’s Source for Adventure in Sudbury, Wilderness Supply in Thunder Bay, and MEC’s online riches wherever you are.

BOULDERING

The subset of rock climbing known as bouldering involves climbers overcoming gravity, but the less threatening type of gravity that only occurs close to the ground. Bouldering is done on short, intensely analyzed routes (called “problems”) on boulders or short cliff faces, such that no ropes are necessary (though crash pads and spotting partners are often employed). By its nature, bouldering can happen anywhere one finds just enough vertical rock, but the most celebrated bouldering area in Ontario is near Niagara Falls, in Niagara Glen. Rules for park access are available here, with problem info here.

TOP ROPE OR LEAD?

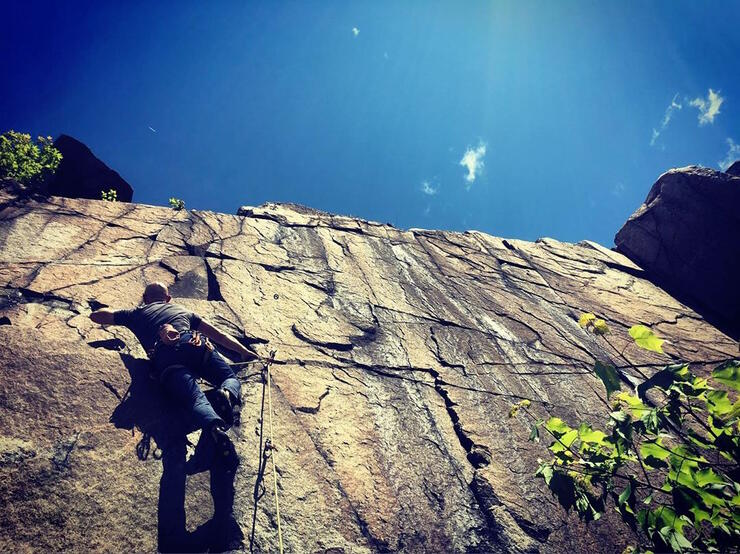

When you are ready to rope up on your own, you’ll need to know the difference between top roping and lead climbing. When you top rope, you begin by setting up an anchor at the top of the route (this requires safe access, of course). The rope that is attached to the climber’s harness passes through the anchor point at the top, before travelling back to the base of the climb, where the belaying partner secures it through a belaying device on their harness. As the climber climbs, the belayer takes up the slack, so any fall is quickly arrested thanks to the anchor point being above the climber.

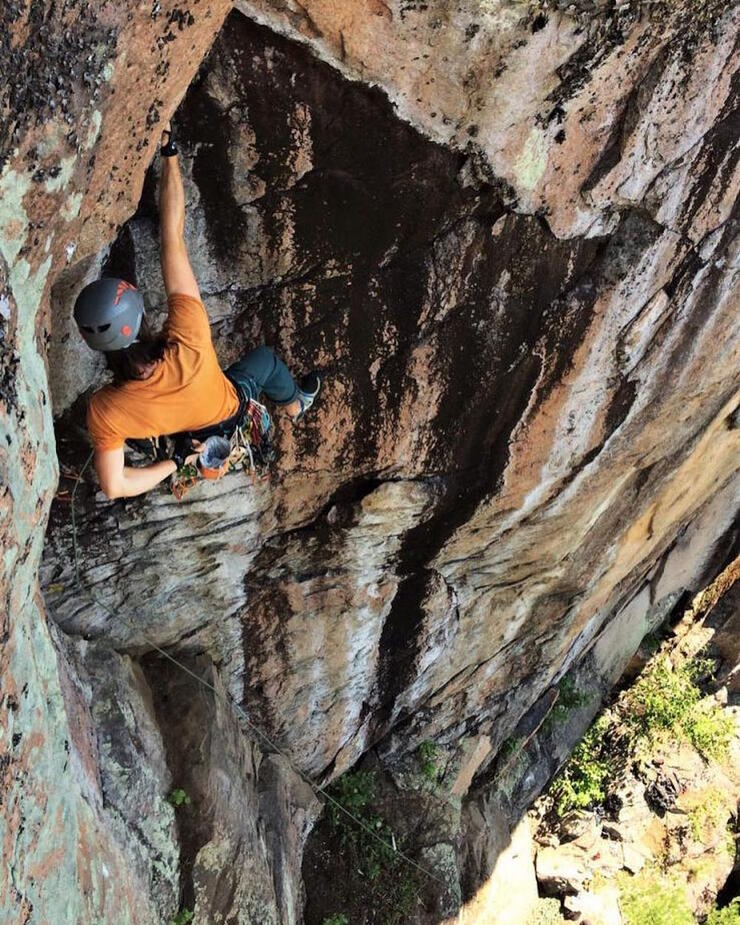

Lead climbing is done from the ground up. The climber and belayer are attached to the same rope, but there is no top anchor involved. Instead, the lead climber places a succession of anchors onto the face as he or she climbs (by way of bolts or nuts and cams—see below). In order to place any new anchor point, the lead climber must climb up past the last point of protection, so any fall will involve more vertical descent before the rope becomes taut.

TRADITIONAL OR SPORT CLIMBING?

Lead climbing on a route that doesn’t have hardware drilled into it requires the setting of “protection.” The climber places specially designed chokes, nuts, or cam devices into any available crack in the rock face, then feeds the rope through this new lead anchor. In the event of a fall, the protection should jam and remain in place when the belay rope becomes taut.

When cracks aren’t available, or when local climbers have access to and an enthusiasm for using a rock drill, you’ll find routes with bolts and hangers drilled into the rock every few metres. The lead climber clips into these by way of quickdraws (two carabiners attached by a short length of webbing).

CARDINAL RULE

Never step on a rock climbing rope. This can grind dirt into the rope and break down fibres. You might hope that the ropes are resilient enough to tolerate this, but by observing this rule you remind you and others that climbers depend on their equipment to safeguard lives.

LEARN THE LINGO

As much as any other sport, maybe more than most, rock climbing has its own language. Here’s a quick cheat sheet on conversational rock climbing-ese.

Belay: One of a number of different systems used by a pair of climbers to stop a climber’s fall or allow a controlled descent.

Beta: Route information.

Crimp: A very small or “thin” hand hold.

Crimpy: A route with lots of thin holds.

Way crimpy: A route with even more thin holds.

Crux: The toughest move of any route.

Jug: A large hand hold.

Juggy: You get the idea.

Pumped: The condition of having your forearms feel like Popeye’s look. Time for a rest.

Rappel: A controlled descent from an anchor, done by running the rope through a friction device on your harness.

REACH FOR THE SKY

Whether you find yourself on southern limestone or northern granite, the wealth of rock climbing routes in Ontario will astound you. As you reach for the sky, we hope you always have a jug when you need it.

Recommended Articles

Trains, planes & Canoes

SKILLS VIDEO: canoe essentials

Need a Father's Day gift?

Want a Leisurely ride?

What's your preference?

"Live from the Rock"

Want style and warmth?

Dog Sledding in Ontario

Fall Animal Viewing in Ontario

Stargazing in Ontario

Adventure Now: Quetico

Outdoor Adventures in Ontario

Happy Tails

Summer Fun Ideas

be inspired on the algoma grand drive

Snowkiting In Ontario

Need Help Travelling?

6 Affordable Family Adventures

WANT A PERFECT CANOEING COMPANION?