The Importance of Art Inspired By Wilderness

Artists can be inspired by almost anything, so with world population doubling from 3.7 to 7.4 billion over the last 45 years, drawing inspiration from wilderness could seem fruitless for anyone and an outright foolish business plan for a professional painter; even an affliction for those near cities like New York or Frankfurt. Of course, the Muse strikes where she will and has famously little concern for whether you can make a living from her wild lead.

Happily for those so afflicted, though not widely known, the largest wilderness on Earth is not in some far exotic land that requires shots to visit and it extends throughout Northern Ontario which is easy to reach from anywhere – and once there, finding your Muse is even easier.

In 1986, I became one of the afflicted. I was a 29-year old freelance advertising artist in midtown Manhattan. I hadn’t meant to be. I had arrived from Vermont with a biology degree and the goal of becoming a nature and biological illustrator. However, even in 1978, Manhattan wasn’t cheap, but field guide and textbook illustrations were. Stealthily, occasional, well-paying ad jobs evolved from budgetary Band-Aids into a high pressure, 120-hour-a-week career. Looking ahead, as people often do approaching landmark birthdays, face-planting onto my drawing board in the middle of a cigarette ad some lonely night loomed as a sad, pathetic fate. Then serendipity struck in the form of a conversation with my brother, Frank.

Frank was born one year after me while our father was stationed with the U.S.A.F. in Kirkland Lake, Ontario (we returned to Vermont when I was two). Married with children ourselves and facing age 30, our talk had nothing to do with my artistic frustrations, but simply that before fattening into adulthood, an adventure was required. We’d grown up camping and canoeing, and a wilderness canoe trip was the immediate choice; a big one. A quick perusal of a road atlas showed few if any rivers in the U.S. that suited, but there was a lot of empty pink paper on the Canadian part of the map. How about the old homestead? We looked around Kirkland Lake and northern Ontario. Any number of meandering blue lines beckoned as they wound northward into imagined wilderness. Seeing one that ran undammed for hundreds of miles to James Bay, we settled on it. Small type on the map listed it as the Missinaibi.

Frank’s duties as a Coast Guard officer prevented him from going that summer (he went with me in ’87), but Dad and I did 95 miles of the upper river to the Spruce Camp 95 bridge upstream of Mattice, Ontario in June. Even without reaching James Bay I was hooked; sensitized to the timeless, wild world that underlies all we know, almost peed on by a bull moose, chewed by mosquitoes, and bitten the wilderness art bug. Despite absurd hours in my Manhattan studio, I stayed up into the dawn for weeks to do two paintings. Canadian wilderness canoe trips became my regular summer tonic for urban life for the rest of my career in New York, and I have been painting wilderness rivers ever since.

Two years later I decided to gradually get out of advertising. Six years later I left and returned with my family to Vermont to plunge headlong into wildlife art. As storybook as that might sound, over several years, the demands of the national wildlife art show circuit had me feeling as much a teamster as an artist and ironically precluded the annual wilderness trips I had done while in New York City. I’d had really good years professionally in 1999 and 2000 but felt adrift. At a show out west in the fall of 2000 I decided to upend my schedule and return to my bedrock; in this instance, not the Green Mountains, but the Canadian Shield. Frank and I had dreamt of paddling all the way to James Bay back in ’86 but never had. It was time to go back to the Missinaibi for a 330-mile (535 km) ‘Source to Salt’ painting trip to reconnect with my Muse.

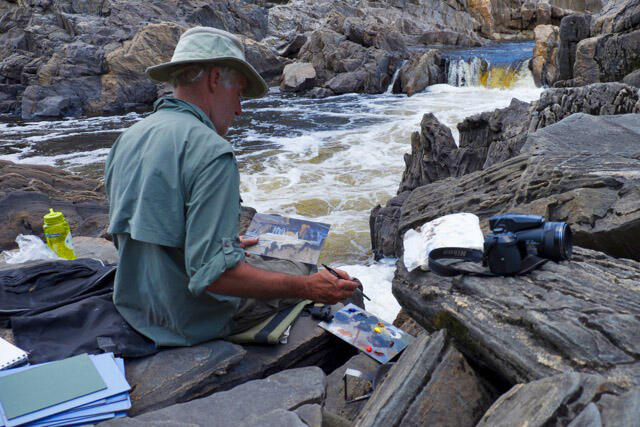

Assuming that no one else would be able to take the time to follow an artist’s itinerary, I planned to travel alone. However, at an art show opening in June 2001, John Pitcher asked to join me. John was (and still is) a leading U.S. wildlife artist and virtuoso field painter (plein air). We set off from Barclay Bay on Lake Missinaibi on August 24, 2001.

Painting with someone of John’s caliber was wonderful. We didn’t do as much plein air as planned due to being slowed by very low water, but we became fast friends and were having a great time sharing ideas for studio paintings and talking of future expeditions with crews of more artists. At Mattice, a nagging hand injury and concern for gallery commitments lead John to regretfully decide to return south. We sat in the Empire Hotel bar as I contemplated continuing solo for the run north to James Bay over a Molson or two. It was far more sobering with the river flowing away into deep wilderness right outside the door than bravely talking about it at artsy wine and cheese parties. However, I was going and I knew it; I just needed reassurance that it wasn’t nuts. John and the beer helped. I waited out three days of rain and set off September 4.

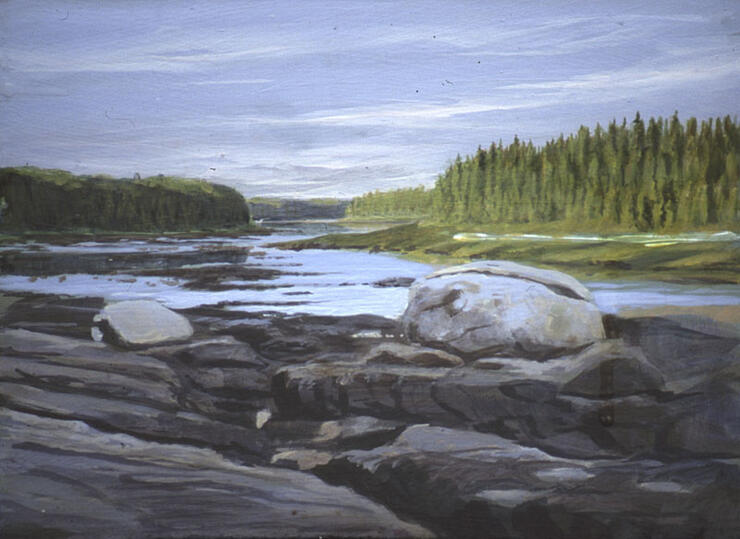

My first evening alone on the Missinaibi River was the most moving painting experience – not the inspiration, but the act of painting – of my life and I suspect it always will be. In all of my paddling, I’d never been north of Mattice before and the solitude lent a potently heightened edge to every stroke and rapid. As I set camp at Kettle Falls portage, it all came down, striking as waves of intense loneliness. Trying to shake it off, I kept to routine and started dinner cooking but the melancholy hung tough. Looking up from the fire and out over the river, the sinking sun was lighting the forest on the far bank. The cook water wasn’t boiling yet, so I grabbed my painting kit and set up. Tending to dinner in between acrylic washes, I focused doggedly to keep the blues at bay and worked fast to catch the light (View North below). Just as I was starting to sense that the piece possibly wasn’t going to be junk, the loneliness very suddenly started to evaporate.

With accelerating relief, it was washed away by a quiet, rising tide of euphoria. Instead of lonely, I suddenly felt connected with everyone. I’ve never heard of a "painter’s high," but that is the best description I can give for it. It seems rather obvious in hindsight, but it had never occurred to me before that painting is such an important part of how I relate to other people. That evening set the track for the rest of my journey north and I did a lot of art.

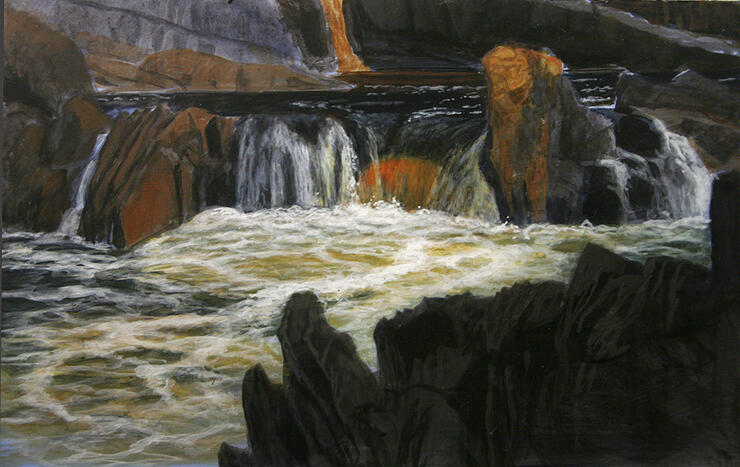

Thunderhouse Gorge is almost too wondrous to enjoy on one’s own, and reaching it the next day, loneliness tried to make a comeback. It was quickly banished for good the following morning by painting two 8”x 10”s next to the upper falls.

In the days after, I kept it up, even managing a couple paintings through a four-day bout of wind, rain, and cold that culminated in a full gale that roared in during the small hours of September 10. It nearly destroyed my camp and continued in full fury all morning. It eased enough in the afternoon for me to move downstream and set a more secure camp. It was still wet, cold, and blowing as I got ready for bed, but to the west, I thought I caught a glimmer of the sunset. What followed was for me as it is for many millions, one of those touchstones of a lifetime. It was art inspired by wilderness, obliterated by human tragedy, and restored by wilderness.

Seeing the gloriously rising light in the morning gave me an insight on how sun-worship arose. The Sandhill Cranes by my canoe were the most incredible icing I could have hoped for and the dawn begged to be painted. It would be a studio piece titled First Light. I did a fast color field sketch and got on the water. Deception Rapid lived up to its billing but was run without mishap, and 31 exhilarating miles later I set camp on Portage Island amid the confluence of the Missinaibi and Mattagami.

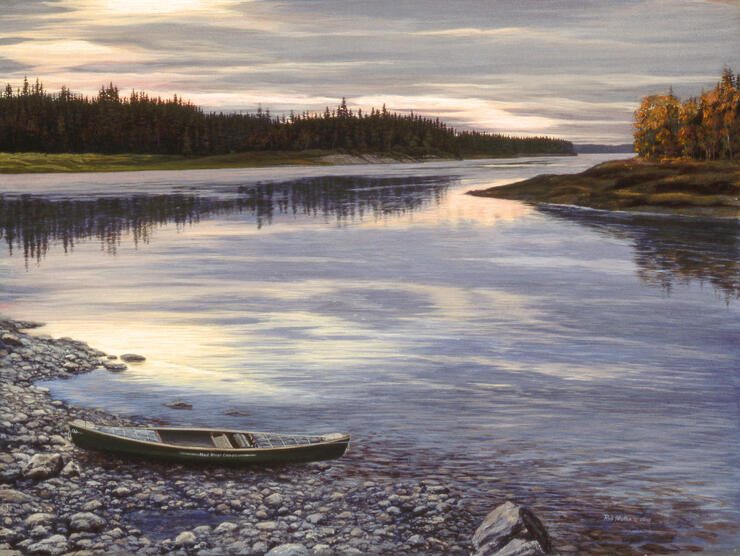

Looking back up at the last of the Missinaibi, 15 years after my dad and I first paddled the upper river, I again painted while tending dinner during what was for me the sublime end of a fabulous day. Happy with the evening field study, I decided to use it as the basis for a studio painting. I already had a title, River’s End. My dinner was shared with friendly Gray Jays and I retired for the night content.

Late the next afternoon, I reached the Ontario Northland RR at Moose River Crossing and learned what September 11, 2001 had been back home. All thoughts of completing the journey, let alone the paintings I yearned to do, crumbled. I knew that Frank’s first day of duty on the Joint Chiefs of Staff in the Pentagon had been September 11, and I was on the next southbound train.

It took a year and a half to start First Light and River’s End.

Resurrecting the motivation to do them required reexamining the original inspiration in light of the human tragedy of that infamous morning. It was thinking back on my time in the wilderness of northern Ontario that restored my resolve. My experience and feelings of that day were no less true because of the tragedies in New York, D.C., and Pennsylvania. On the contrary, they underscored the beauty, potential, and promise of the natural world that sustains us regardless of the horrors we inflict on each other. Tragedy and wonder coexist every day; and they did even on that day.

In the years since, John’s and my idea of artist crews on subsequent expeditions has come true. I’ve run 18 wilderness art expeditions from Labrador to Alaska since 2001 (John came on two more of them and Robert Bateman came on one). However, I never finished the seminal journey to James Bay. In 2003 we tried again, wanting to test if a late September/October trip was feasible. It wasn’t. The rain only stopped when it snowed and the journey ended again at Moose River Crossing. That all finally changed in July and August of 2016; 30 years after my first trip with Dad.

On July 29, British Columbia wildlife artist Julia Hargreaves, Vermont professional nature photographer Stephen Gorman, and Amherst College ecology student JJ Daniell returned with me to Mattice to finally complete the run to James Bay. It was a far different journey. It was warm (hot, actually), we all had company, and there was none of the high drama of the 2001 trip. Yet for an artist, that didn’t matter; a wilderness river always provides inspiration. Julia and I completed a nice body of work on the journey and Stephen and JJ captured stunning images.

I’ve now done various parts of the Missinaibi six times and have had a "trip of my life" every time. The Missinaibi is unique and wonderful every day and no matter how familiar, is always new and inspiring. However, there was one part of this trip that was not familiar. On August 10, we passed the RR bridge at Moose River Crossing and continued north. On August 12, we ground ashore below the historic Hudson Bay Staff House at Moose Factory across from Moosonee. Before heading home on the Ontario Northland Polar Bear Express, we hired a Cree motor canoe to take us the last seven miles out to open water.

There is a freedom in completing a long-held dream, and the wide-open horizon of the Arctic Ocean embodied it.

As I learned at Thunderhouse in 2001, such moments are meant to be shared and it was heartwarming to reach the end of this journey in such good company. Now we’ll see what comes out of the studio.

FIND OUT MORE

Recommended Articles

March Break in Ontario

Crown Land Camping

Natural Highs

Destination Dupes

Backpacking Trails in Ontario

Ontario's Best Family Resorts

Dogs Welcome!

Explore Ontario’s Hidden Gems

2025 Triathalons

11 Jaw-Droppingly Beautiful Landscapes

Insider’s Guide to Sleeping Giant

Best Cross Country Ski Spots

Cold nights

25 Adventurous Fall Activities in Ontario

Tips for 2026 Camping Reservations

The Best Camping In Ontario

Call Us Crazy

Girls’ Getaways

Where to See Ontario's Coolest Wildlife