On Your Mark, Get Set...

It happened this past weekend in Northwestern Ontario, and in many other areas across Northern Ontario. No, not the Santa Claus parade. Many of the small and moderate size lakes froze over, making ice anglers light-headed with anticipation.

So giddy, in fact, that I've been fielding email messages from ice anglers to the south of us who are biting their lips in eagerness. The hard water brigade wants to know if the ice is safe enough yet to venture out on, and if it is not, when do I think it will be.

If you're wondering how soon it will be before the ice on your favourite Northern Ontario walleye lake is good enough to walk on, check out Gord Pyzer's formula in this blog.

In a word, the answer is "no," the ice is definitely not thick enough yet to walk on. The good news, however, is that by monitoring the air temperature and wind speed in your home area, you can use a very simple and cool—sorry, pun intended—mathematical formula to predict when your favourite Northern Ontario lake will be safe to fish.

Many of the small and moderate-sized lakes in Northern Ontario have started freezing over, making ice anglers giddy with anticipation.

Here is how you can do it—or better yet, if you have kids at home who are chomping at the bit to go ice fishing, how you can put them up to the arithmetic challenge.

Start by taking the average temperature (in degrees Fahrenheit) over the past 24 hours. Let’s say that the daytime high yesterday was 30° F and the nighttime temperature last evening was 20° F. This means the average temperature was 25° F. Now, subtract the average temperature (25° F) from the freezing point of water (32° F) and we get 7°... or more importantly, seven freezing degree days (FDDs).

That was simple, right?

Now, everything kicks into gear when your favourite lake first develops a thin coating of ice. From this stage on, the ice will typically increase in thickness at the rate of one inch per 15 freezing-degree days (FDDS). So, if we go back to our example, this means that if there were seven FDDs over the last 24 hours, the lake added about half an inch of ice.

Of course, we know that ice builds up more quickly when there is a slight to moderate breeze, no snow on the surface, and clear skies. Snow, in fact, acts like a thermal blanket and serves to keep the frost from penetrating the surface of the lake and the ice. As a result, deep snow cover will slow down the ice formation process significantly.

Small and moderate-sized stocked trout lakes usually offer the best early-season bets for the eager ice angler.

Indeed, as I've mentioned in the past, this is why lakes in the high Arctic don't freeze into a solid block of ice. At some point, the snow and thick ice act as a down jacket to stop the water from freezing any further.

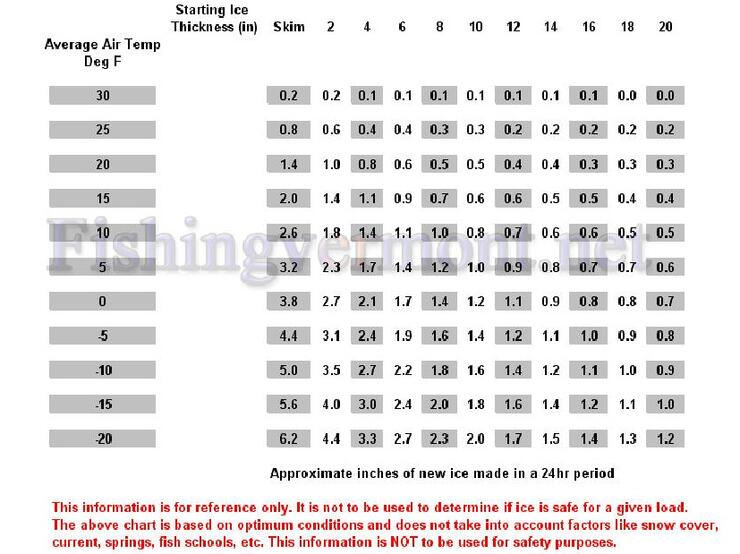

Over the past couple of winters, I have found this formula to be an extremely accurate way to keep track of how much and how fast the ice is forming and building up on my favourite walleye, trout, crappie and yellow perch lakes. And I've been able to keep even more detailed diaries using the following chart, developed by my buddy Bob Dostie, who has incorporated information and data that he obtained from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

So, forget the Santa Claus parade—the good news is that many of the lakes across Northern Ontario are now finally covered with ice. And if you keep track of the high and low temperatures each day, you can accurately determine how fast it is building up.

With that in mind, charge the battery in your snowmachine, add gas line antifreeze to the fuel tank, gather up your ice fishing gear from the rafters in the garage, and start sharpening your hooks. The hard water ice fishing season is about to begin across Northern Ontario.

Recommended Articles

Ontario Brook Trout

Top 5 Flies for Smallmouth Bass

Dream Fishing Trips

3 Great Ontario Walleye Destinations

Eating Northern Pike

The Big Bass List: 5 Incredible Hotspots in Northern Ontario

Speckle Splake Spectacular

Top 10 Streamers for Ontario Brook Trout

Shoreline Strategies

Balsam Lake Walleye

Accessible Paradise

Catching Ontario Walleye

Birch Dale Lodge

Smallmouth Bass With Still Water Fishing and Tours

5 Lakes, 4 Seasons, and Plenty of Fish

Four Seasons of Bass in Ontario

20 Years With Fish TV!

Kashabowie Bass Blast

3 Surefire Strategies for Canadian Muskies