Gunilda's Life on the Water

During the 14 short years that the steam yacht Gunilda graced the waters it served as a symbol of the Gilded Age's ultimate luxury and spirit of adventure. Its voyages weren’t merely travels across the sea; they were grand adventures that captured the essence of a time when the affluent aspired to rule the waves with the same force they did the land. The Gunilda’s history is just as rich and illustrious as the ship itself. Despite its untimely fate 270 feet (82 m) below the surface of Lake Superior, the Gunilda lives on as a fascination for an era gone by.

Construction

The Gunilda’s inception was the result of a commission by J.M. Sladen from England. The renowned yacht brokerage and design firm Cox & King entrusted the design to their naval architect, Joseph Edwin Wilkins. Known for his elegant yacht designs, Wilkins’ work contributed significantly to Cox & King’s reputation in the luxury yacht industry. For an insight into their craftsmanship, the Cox & King Catalogue of Yachts and Motorboats showcases their designs.

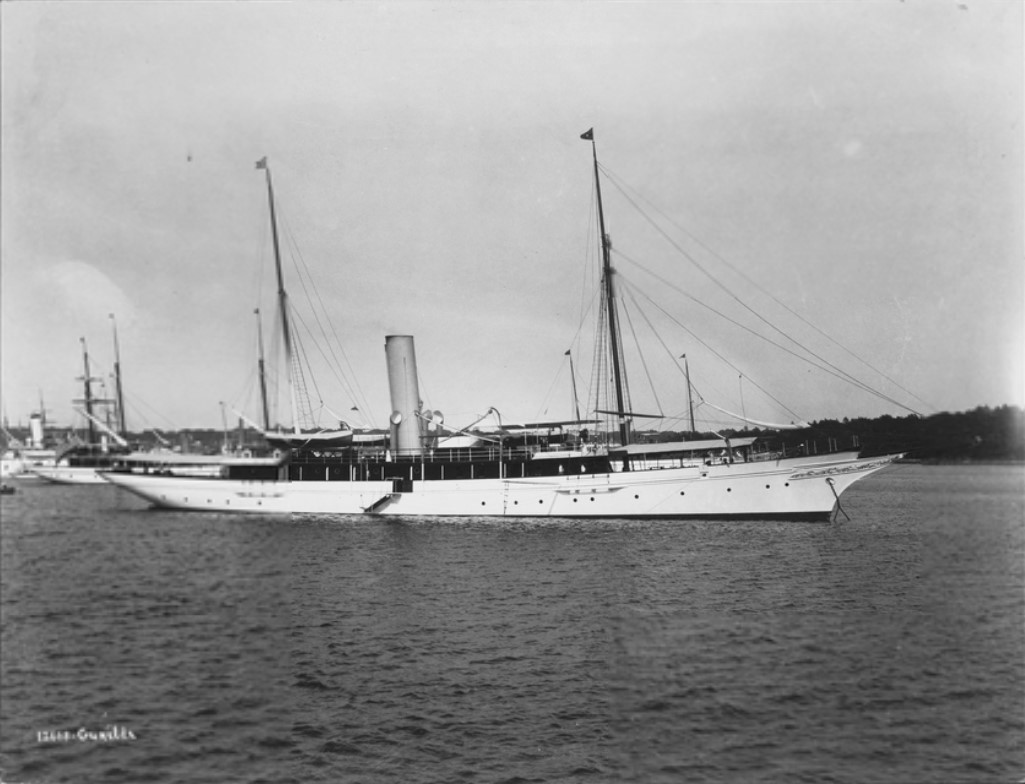

Constructed in 1897 by the shipbuilders Ramage & Ferguson out of Leith, Scotland, the Gunilda had a cost of around $200,000. Adjusted for inflation that would be equivalent to approximately $7,555,373 in modern currency.

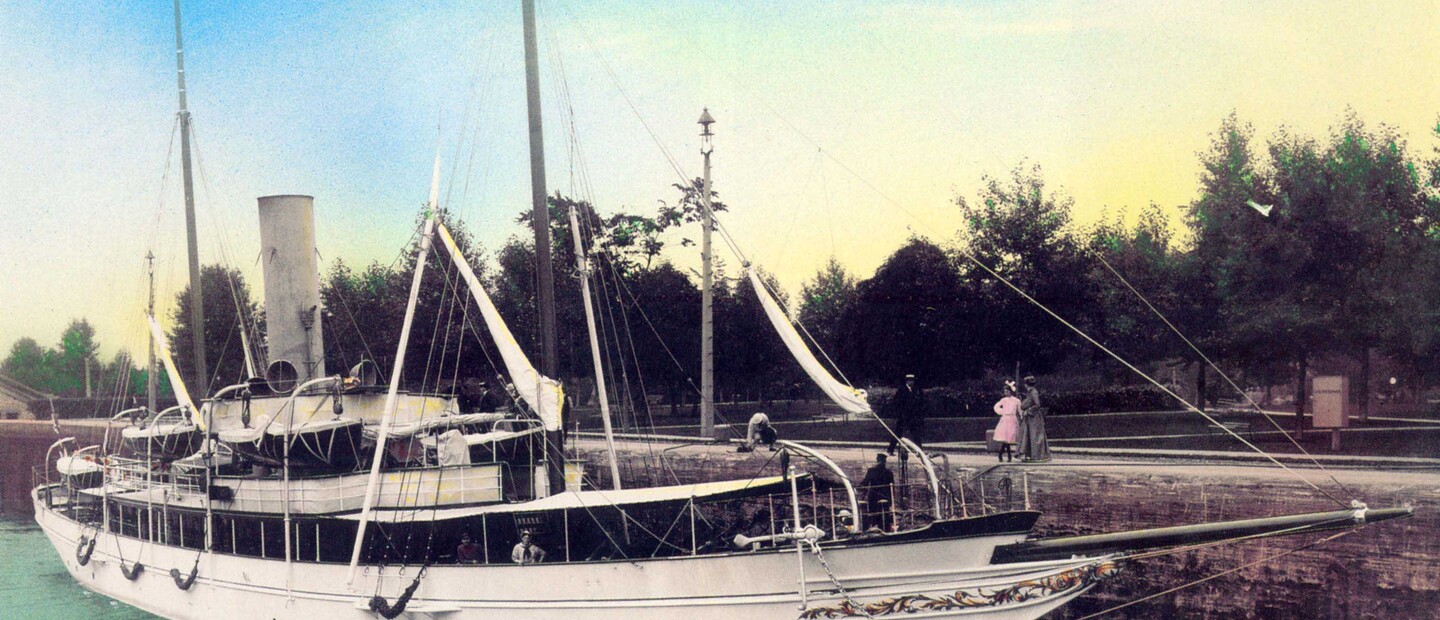

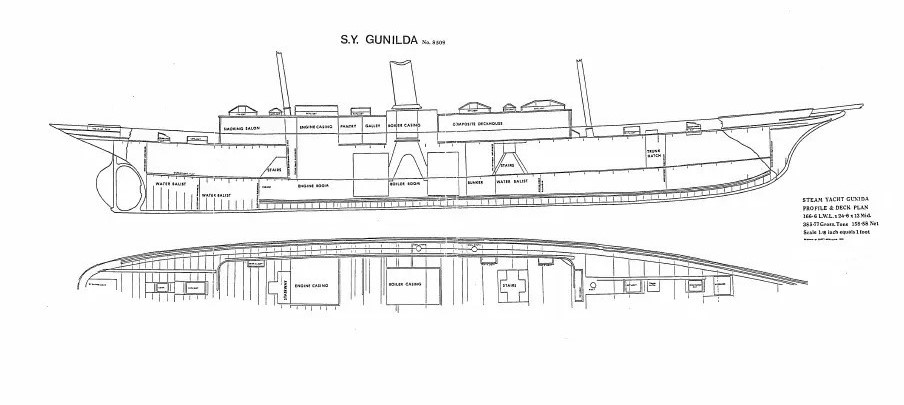

The opulent yacht spanned an impressive 195 feet (59 metres) in length, weighed 385 tonnes, and had a speed of 14 knots. Its bow featured elaborate scrollwork, gilded with gold leaf. The interior rooms included an elegant parlour complete with a grand piano, a cozy fireplace, and a sunroof that bathed the room in natural light. Each private cabin was elegantly appointed with guests' comfort in mind for long journeys.

The name Gunilda is derived from “Gunhild”, a feminine German name that is often associated with the concept of "war". However, upon further investigation, it appears that the name more accurately translates to "fighter."

Owners

The Gunilda had a few owners during its 14 short years on the water. As previously mentioned, the Gunilda was initially commissioned by J.M. Sladen from England in 1897. The following year, it changed hands and became the property of F.W. Sykes also in England. Not much is known about these men or what kind of voyages they had with the Gunilda although it was common for yacht owners at the time to be part of an exclusive yacht club or even participate in racing and wagering.

In 1901, a member of the New York Yacht Club chartered the Gunilda across the Atlantic to New York. It was quite an undertaking and required a crew of 25 and approximately 10 to 14 days to cross the ocean. In 1903 the Gunilda caught the eye of wealthy oil baron, William L. Harkness of New York. He purchased it and brought it under the flag of the New York Yacht Club and it became the club's flagship for its grandeur and size. It was Harkness whose ill-advised decisions led to the unfortunate sinking of the Gunilda.

Voyages of the Harkness Family

William Harkness didn't miss an opportunity to enjoy leisurely trips and explore the waters on the Gunilda. He took multiple trips across the Atlantic and Caribbean. Likely docking at places such as St. Thomas, the Bahamas, and Isle de Sol in Sint Maarten whose marinas could accommodate large luxury yachts. These voyages would have no doubt been grand affairs with elaborate parties aboard. The Gunilda would have evoked awe and fascination from every vessel it passed and every harbour it docked at.

In 1910 Harkness sailed the Gunilda into the Great Lakes. The summer of that year brought him to Lake Superior where he sailed along the southern coast to Duluth, Minnesota. The Duluth Harbor was bustling at the time, with significant improvements to aid navigation having just been completed. The Duluth Harbor North Pier was constructed on the breakwater of the Duluth Ship Canal and has been a cherished maritime landmark ever since. Harkness enjoyed his time on Lake Superior so much that he decided to return up the northern coast to the city of Port Arthur (now Thunder Bay) the following year.

The Return to Lake Superior

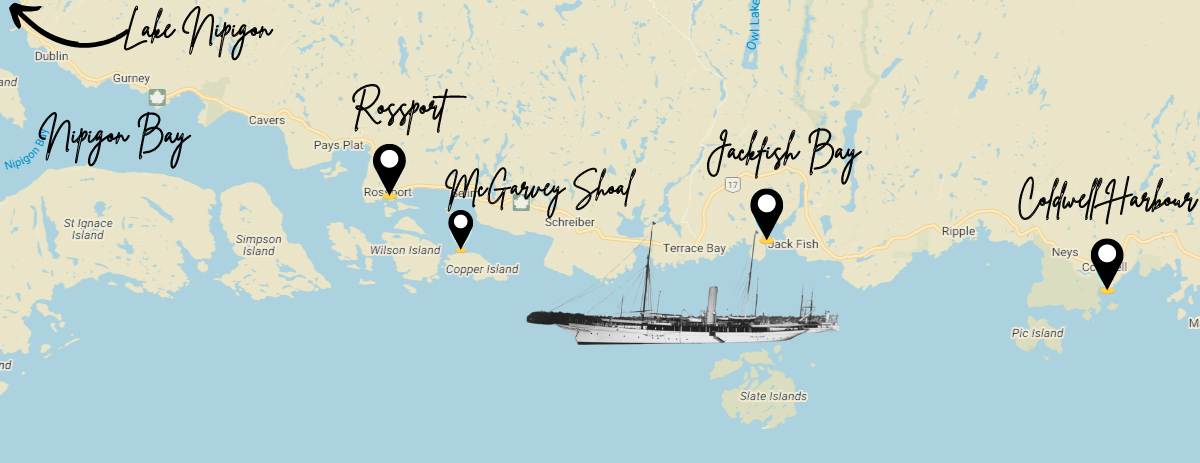

In August 1911, the Gunilda returned to Lake Superior. There were 36 people aboard on this particular voyage. Harkness, his wife Edith, their two children Louise and William, another wealthy family, J.D. Harding, with his wife and son, Captain Alexander Corkum, and the crew. Lake Nipigon was increasingly becoming renowned for its excellent recreational and commercial fishing industry. Harkness enjoyed fishing during his explorations on the Gunilda (see photo above) and decided he wanted to divert to Lake Nipigon to fish for speckled trout.

The American nautical charts onboard the Gunilda indicated that they would have to go through the Schreiber Channel, to Rossport, then up to Nipigon Bay. They would have to navigate through the Rossport Archipelago to do so—the largest group of islands on Lake Superior.

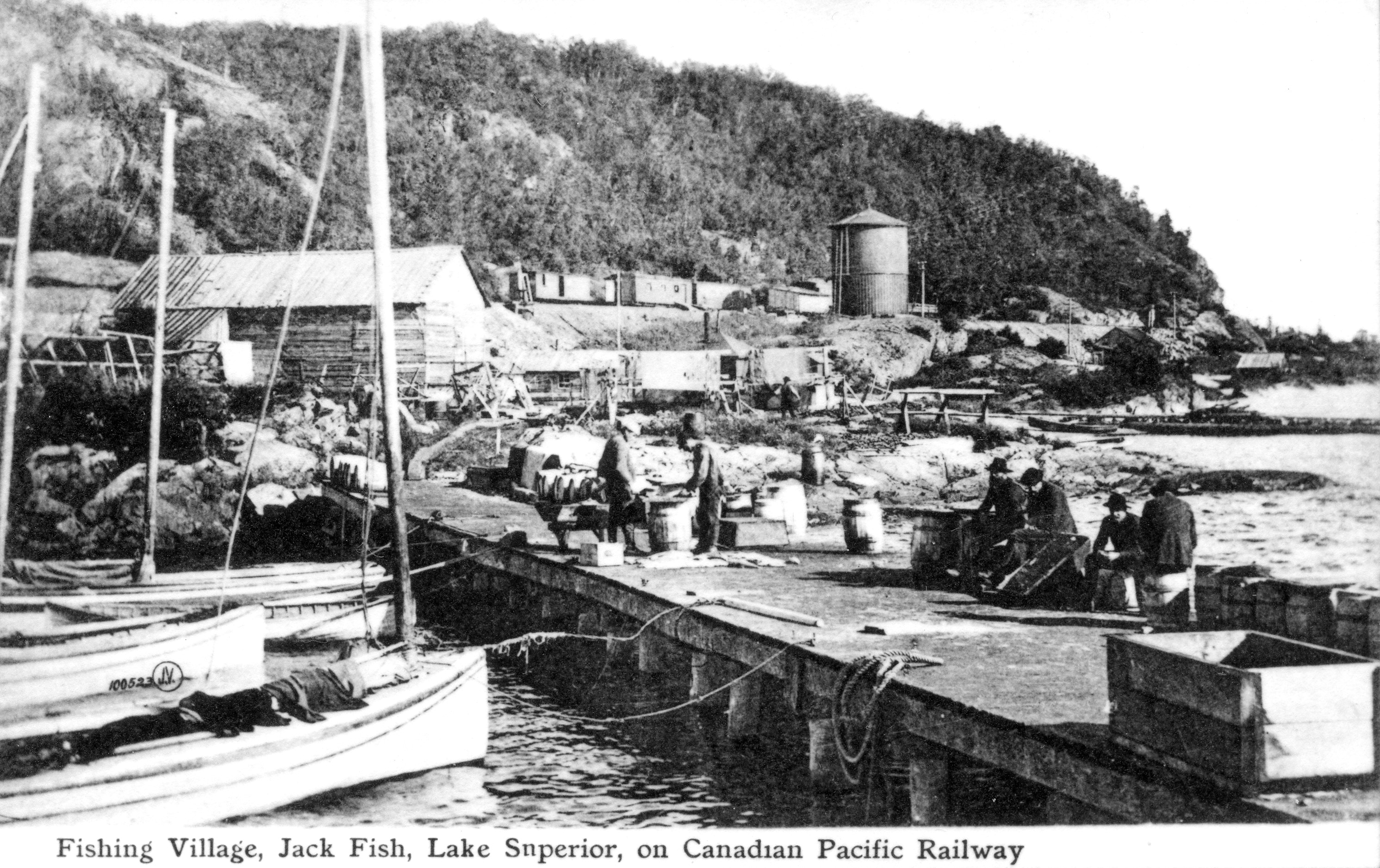

The villages dotting the north shore of Lake Superior were primarily fishing villages. The locals were quite experienced and knowledgeable about the safest water routes. When the Gunilda docked at Coldwell Harbour, Harkness asked around for a pilot willing to guide them to Nipigon Bay. A local man named Donald Murray who was very experienced on the water offered to take on the task for the cost of $15. Harkness thought that it was far too much for such a service. He was confident that he would be able to haggle for a lower price at Jackfish Bay the next day where they were stopping to load coal. Jackfish Bay resident Harry Legault said he would take them to Rossport for $25 plus the cost of train fare back. Harkness again refused the offer much to the dismay of the captain and crew. This would turn out to be a grave mistake as their American charts didn't indicate any shoals to watch out for.

The Beginning of the End

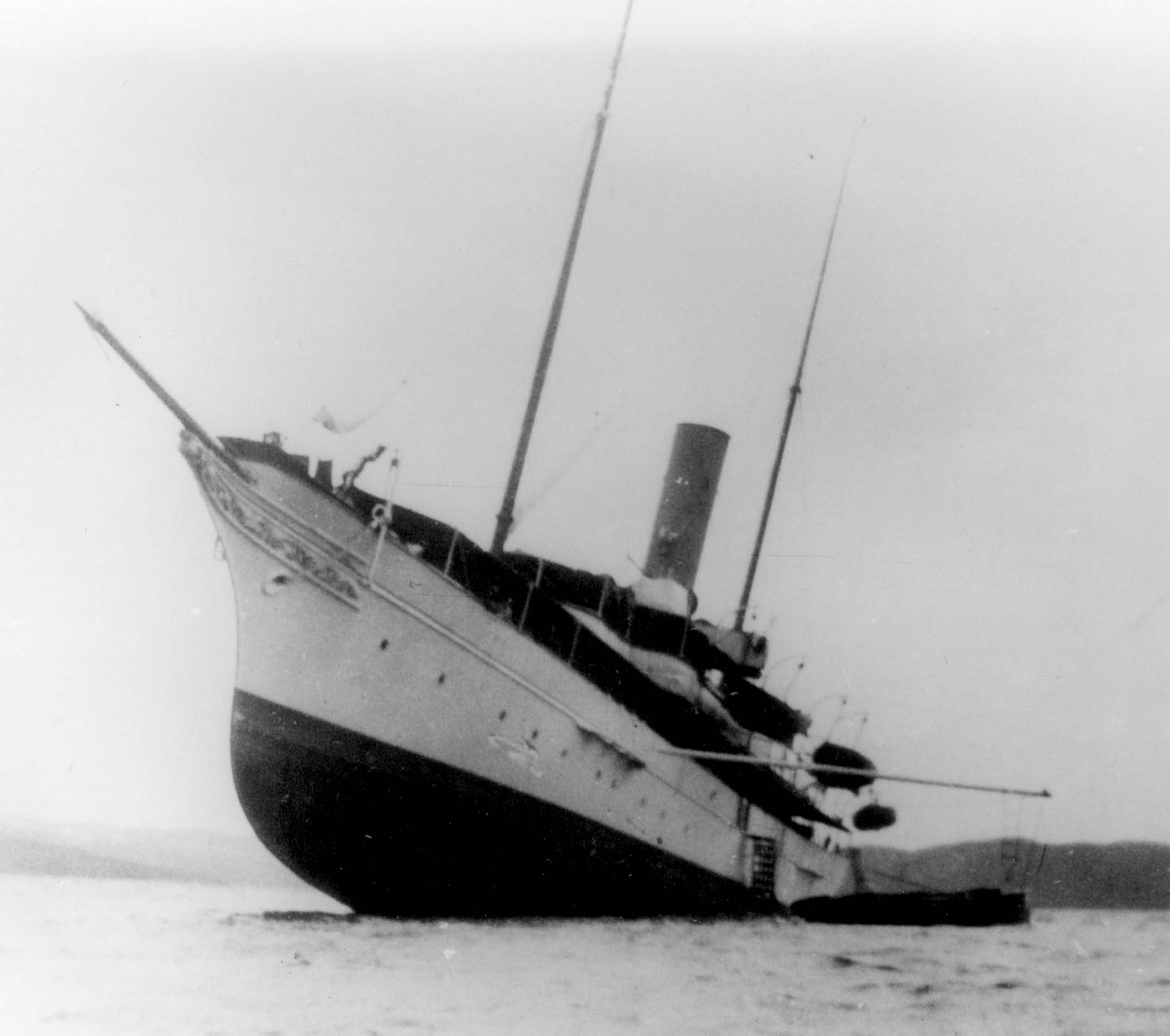

Had they been equipped with an accurate map, they would have been aware of the McGarvey Shoal marked just north of Copper Island. Instead, being unaware of any potential obstructions, the Gunilda ran aground on the shoal at maximum speed. The impact drove the yacht so far onto the bank the bow was dramatically elevated above the waterline.

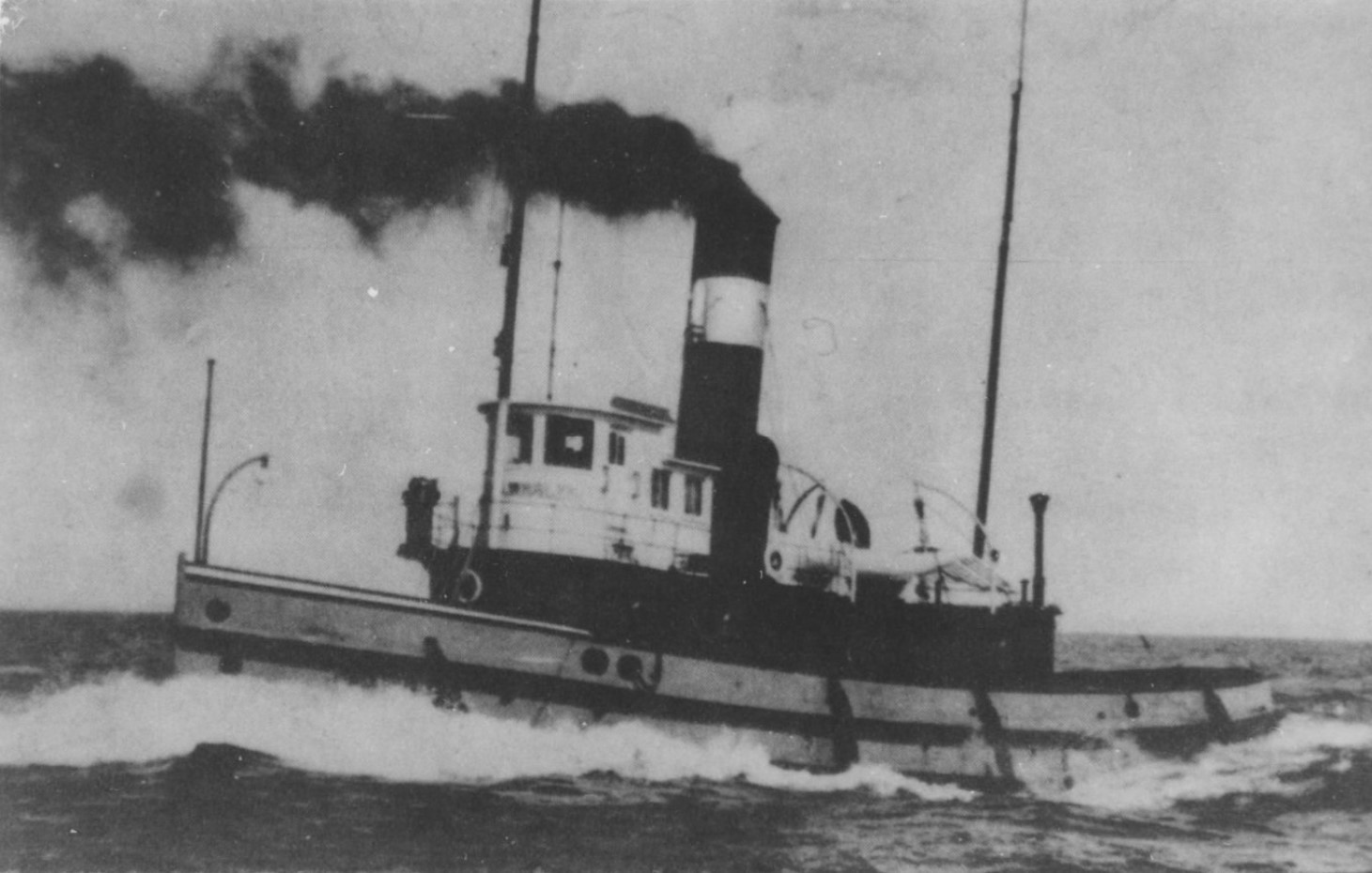

At that moment one would think that Harkness would have regrets about not hiring an experienced guide. The following events prove that might not have been the case. Having no immediate way out of this bind, all the passengers were brought safely to Rossport about 5 miles (8.0 km) away on a tugboat. They left behind all their belongings fully expecting to return to the Gunilda once it was freed.

Harkness contacted the tug James Whalen from Port Arthur to release the Gunilda. It was the largest and strongest tug on Lake Superior. When they arrived and assessed the situation, Harkness was advised that it would take two tugboats to free her. The second tugboat would help stabilize the yacht while being pulled off the shoal. Harkness thought that only one would suffice and refused to pay for a second tugboat. This refusal to take yet another expert’s advice turned out to be his third mistake.

With only one tugboat the Gunilda was pulled off the shoal and immediately keeled over as predicted. Tilting starboard, it quickly started taking on water through the open port holes and doorways. It only took a few minutes before the massive luxury yacht was completely submerged and sank 270 feet below the surface of Lake Superior on August 30th, 1911. There it remains to this very day.

Gunilda's Next Chapter

While that may have been an end for Gunilda, it was not the end. In 1967 it was rediscovered by a diver named Chuck Zender. This discovery set off a fascination for this elaborate and fully intact shipwreck by any technical diver who hears about its lore. There have been attempts to raise the Gunilda and many technical divers have been lucky enough to witness it themselves and some were not so lucky.

But those are stories for another day.

Recommended Articles

10 Reasons to *NOT* Travel the Lake Superior Circle Tour

Canoeing the the Slate Islands near Terrace Bay

6 Amazing Facts About Red Rock, Ontario

11 Things to Do in Silver Islet, Ontario

Incredible Fishing at Dog Lake Resort

Best Roadside Picnic Spots in Northern Ontario

A Father and Son Tradition at Miminiska Lake Lodge

Hikes, Bites and Sights on the North Shore of Lake Superior

A Day Tripper's Guide to Nipigon

A Historic Lodge in Red Rock, Ontario

Hunting for Yooperlites Along Lake Superior