Hit The Hard Rock Cafe

Every winter it seems—right across Northern Ontario—one fish or another falls madly in love with the conditions. Usually, it is an apex predator like lake trout or walleye, but this winter the panfish are doting on the state of affairs. And it is not just in my Northwestern Ontario Sunset Country neck of the woods. I’ve got friends 2,000 kilometres away who are ice fishing on Lake Nipissing and Lake Simcoe and enjoying the same hot winter bite.

Follow the fish in mid-winter and you’ll enjoy dazzling days on the ice in Northern Ontario. (Photo credit: Gord Pyzer)

As a matter of fact, I’ve caught a big slab crappie or fat jumbo perch on the first drop down the hole on my last five trips. And I’ve not gone back to the same spot yet this winter. It is an exciting way to start the day and keep your confidence riding high, especially as we progress into the concocted February doldrums.

Panfish relate to soft bottom areas where there are prolific populations of insect larvae, scuds and spiny water fleas. (Photo credit: Gord Pyzer)

I say concocted because as long as you move with the fish, you can always catch them. But if you don’t adjust, you’re fishing empty water, so you might as well blame it on the calendar.

Case in point, at first ice back in early December, my grandson Liam and I got into a beautiful bunch of fat feisty perch precisely where we had left them at the end of the open water season. They were still in 24 feet of water up on top of a rocky saddle that connects two islands. But those fish have now moved away from the hard boulder-strewn apex, dropped down the side of it and are now finally relating to my favourite place to catch them—the hard/soft transition. Or as I like to call it—the Hard Rock Cafe.

Follow the fish in mid-winter and you’ll enjoy dazzling days on the ice in Northern Ontario. (Photo credit: Gord Pyzer)

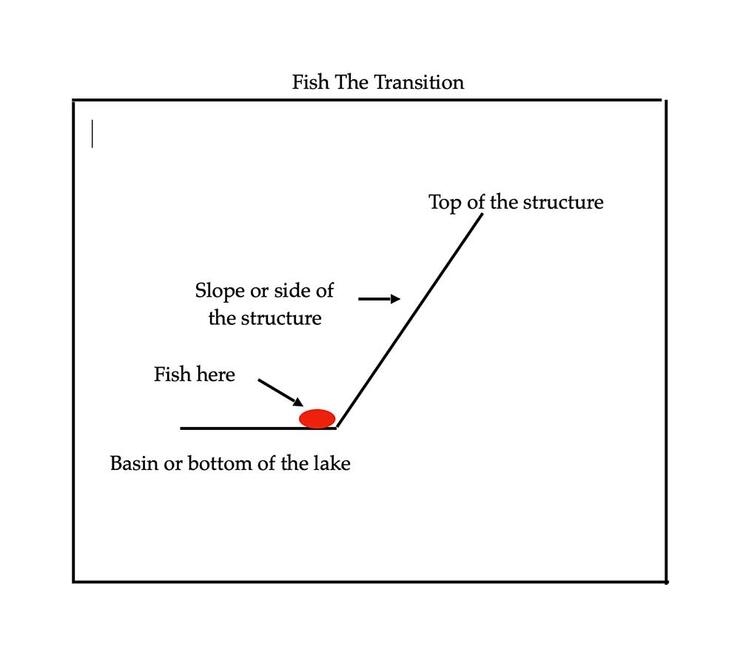

The best way to understand what you’re looking for right now is to visualize a hockey stick. The end of the handle is the top of the structure—the reef, shoal, rock pile or saddle—where you found the fish two months ago. The shaft, on the other hand, is the side of the structure that slopes down to the basin. And where you want to be fishing right now is where the shaft meets the blade. Oh, my, how it bunches up the fish!

In mid-winter the key spot on most structures is the area (in red above) where the side of the structure merges with the basin. (Photo credit: Gord Pyzer)

I am not entirely certain why the perch and crappies make this move every winter, but I know from checking their stomachs that it involves their diet and changing food sources. Early in the winter, for example, when Liam and I were catching them up on top of the rocky structures, their stomachs were full of small fingernail-sized crayfish and minnows. But now they’re oozing indistinguishable soft grey mushy matter that, when you look at it closely, you can see the tiny eyeballs and antennae of nymphs, scuds and spiny water fleas.

The burrowing insect larvae live in the soft bottom — especially when it is like pottery clay — and while you’ll find some along the slopes, it is typically only a few inches thick. But when you reach the transition, where the shaft meets the blade of the hockey stick or where the side of the structure meets the basin of the lake, it is soft, thick and gooey. So rich and teeming with microscopic life that is not uncommon to shift through 1000 mayfly or midge larvae (bloodworms) in every square metre of the lake bottom. Talk about a fishy smorgasbord or an all-you-can-eat buffet.

If the lake you’re fishing has an enhanced Lake Master map, finding the transitions with your chart plotter is a breeze. If your favourite lake hasn’t been charted with one-foot contour intervals, though, the normal map will still put you close to where you want to be. You just need to drill a few extra holes so you don’t get shafted.

Gord Pyzer’s favourite place to catch jumbo perch and black crappies is the Hard Rock Cafe. (Photo credit: Gord Pyzer)

Indeed, I hate—detest is more like it—fishing on the slope for two reasons: first, the crappies and perch don’t like it, preferring the flat soft basin bottom, where they can peck away like barnyard chickens. The second reason, however, is that you can’t see your lure. It is lost in the dead zone along the slope when your transducer reads between the high and low spots. So, space out your holes and keep drilling until the bottom is as flat as a pancake when you drop the transducer into the hole and watch your lure descend.

Welcome to the Hard Rock Cafe.

In Part 2, next week, we’ll wrap up with everything you need to know to put those fat jumbo perch and dinner-plate-size crappies on the ice.

Recommended Articles

Wild Brook Trout

Beating the Blues

Fishful Dreams Do Come True

Labour Day Lunkers: Why Fall is the Ultimate Time for Lang Lake Bass

Irregular Lake Trio

Chiblow Lake Smallmouth Adventures

A Guide to Fly-in Ontario Lodges

Pro Fishing Photos

Casting for Coasters

Agich's Kaby Kabins

Destroying Fall Muskie Myths

Long Nose Gar

Four Seasons of Bass in Ontario

Family Fishing Getaway

Flying in for Ontario Northern Pike

Miles Bay Camp

Cat Island Lodge

Kicking It Old School

Top 5 Tips To Fish Smallmouth Bass in Ontario