The History of the Fire Tower: From World War II to Jack Kerouac to Temagami

The history of the fire tower—once an essential piece of infrastructure for countries all over the world—is a fascinating one. Nearly every country with large tracts of forested land—including, of course, Canada—have utilized these simple structures to detect and report forest fires before they get out of control. Residents of Northeastern Ontario may be familiar with the famous Temagami fire tower, now a tourist attraction and a beloved part of the area’s skyline.

At their peak, the towers sprawled throughout North America, with 325 lookouts across Ontario alone. In the U.S., Idaho had 966 known towers, the most of any state. Over the last century, however, as satellites, infrared technology, and tanker airplanes have revolutionized firefighting and made operational fire towers increasingly rare, these structures have nevertheless maintained a sense of mystery in our popular imagination. (Fire towers even appeared in the popular CBC show Forest Rangers, with filming taking place at towers in North Bay, Dorset, and Bracebridge.)

Remote, often inaccessible, these quirky towers draw just as many curious visitors today as they did back when Jack Kerouac holed up in one in the summer of 1956.

The Origins of the Early 1900s Fire Tower

The use of fire towers coincided with the burgeoning logging industry, but also a growing awareness about the need for conservation, preservation, and more consistent land management in North America—which meant no more massive forest fires burning unattended. Parks Canada, founded in 1911, was the world’s first national parks service, followed by the United States National Park Service in 1916. Fire towers would play an important role in protecting the national parks (and the valuable timber) of both countries in the years to come.

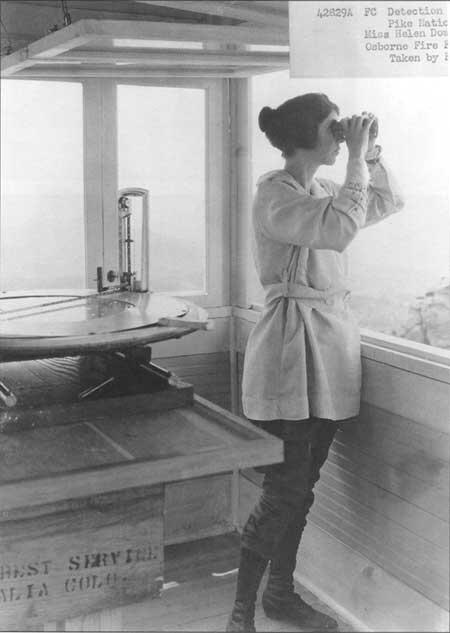

The idea was simple: Build a tall structure on a hill or mountain peak, hire someone to live in it, and have them report fires to teams on the ground. This inexpensive early warning system was invaluable to the logging companies as well as any municipality at risk of damage by fire (which in the early 1900s Canada was basically all of them). News of the fire was transmitted by the lookout via a heliograph (Morse code using two mirrors and the sun), carrier pigeon or later, via telephone. The exact location of the fire was determined using an instrument called the Osborne Fire Finder.

“The mere fact that a tract is carefully watched makes it safer, because campers, hunters, and others crossing it are less careless on that account,” wrote Henry Graves, chief of the United States Forest Service. “By efficient supervision most of the unnecessary fires can be prevented, such as those arising from carelessness in clearing land, leaving campfires, and smoking.” With more federal programs for fire spotting in place, fire towers sprung up all over.

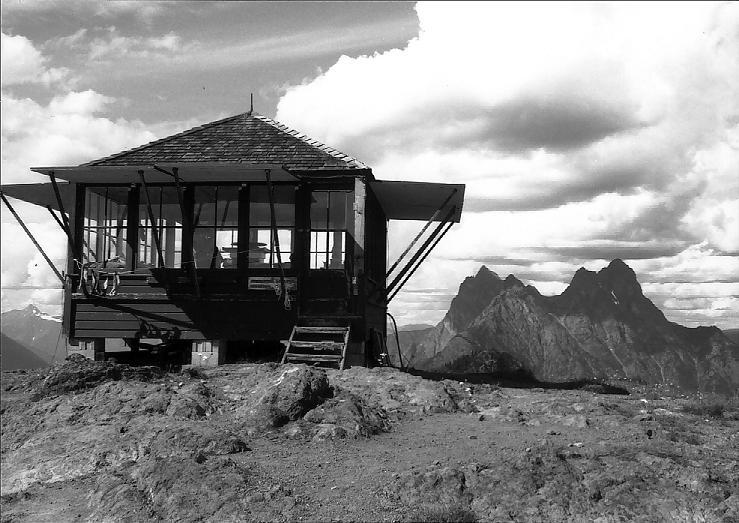

Styles of the towers differed depending on the country and terrain, but in North America, a lookout was usually a raised wood cabin, a wood or steel tower, or simply a tree. On mountain peaks, the lookouts were often basic cabins with living quarters below and an observation room above accessed by a ladder. In more forested terrain, wood, and later steel, was used to build a tower with a small platform for the lookout to live.

The Gloucester Tree in Australia is, well, a tree. Consisting of 153 laddered spikes in a giant karri tree with a wooden lookout cabin on top, it’s the second-tallest fire lookout tree in the world. Today, it’s open to the public—but 80% of visitors chicken out before reaching the top. Every design, however, allowed the fire lookout unrestricted, 360-degree views of the surrounding landscape.

Working the Towers

The people who lived and worked in the fire towers over the years were an interesting group—loners, single men and women of all ages, couples looking for adventure, and artists looking for inspiration. Beat poets Gary Snyder and Philip Whalen both worked as fire lookouts in the 1950s. But perhaps the most famous resident in the history of the fire tower was Jack Kerouac—the author spent the summer of 1956 manning a fire tower on Desolation Peak in Washington State. Alone in the tower for 63 days, the writer translated his experiences into works like The Dharma Bums, Desolation Angels, and Lonesome Traveler. (Kerouac was also supposed to be recording each aircraft he spotted on an official form provided by the Air Force—but he used the paper to roll his cigarettes).

According to the author of “A History of the Architecture of the USDA Forest Service,” those “who spent their time in these remote, isolated forest environments had to be self-contained people with a sense of humour.” The following poem, written in 1948 by a lookout in Washington’s Colville National Forest, is an example:

think they're mighty fine.

One rolled off the table

and killed a pal of mine.

I like FS coffee;

think it's mighty fine.

Good for cuts and bruises

just like iodine.

I like FS corned beef;

it really is okay.

I fed it to the squirrels;

funerals are today.

Since many of the lookouts were initially manned by young single men with little experience cooking for themselves, branches of the U.S. Forest Service even released basic cookbooks to help the men survive with recipes for bean soup, salmon loaf, and Jell-O.

Being a lookout wasn’t just writing poetry and cooking salmon loaves, however. The job could be dangerous as well. “Mid-August 1941, on Fir Mountain, brought the worst storm I was to experience,” wrote one resident in his journal. “I saw at least 10 smokes on the adjoining ridge, my telephone went down, and rocks sprayed the station. The storm was under me, over me, and deafening—lightning almost constant and terrifying.”

More recently, 70-year-old Alberta fire spotter Stephanie Stewart (Alberta still has around 125 operational lookouts, manned every summer during peak fire season) vanished from her post in 2012. After failing to call in her morning report, Stewart’s supervisor went to check on her. A pot of water on the stove remained warm, but Stewart had vanished. The case remains open and the $20,000 reward for information is unclaimed.

The Fire Tower in Modern Times

From enemy aircraft lookouts to quirky hotels, fire towers have served some unusual and essential services over the years. (In the 1940s, fire lookouts from across states like California, Oregon, and Washington, were enlisted as enemy aircraft spotters during World War II.) More recently, as fire towers were decommissioned and abandoned, many remaining towers have become tourist attractions. Of course, manned fire towers remain an essential first-line tool against forest fires and they are still in use in many countries today.

Those looking to have their own fire-tower experience can head to the Temagami Fire Tower atop Caribou Mountain—100 feet tall and made of steel, it’s just waiting for visitors to climb to the top and enjoy the view. It’s a great spot to visit for views of the surrounding landscape at any time of the year.

Recommended Articles

The Seven's Best Hikes, Biking Trails and Lakes

7 Best Spots to Check Out in The Seven

Budget Bliss: Explore Northeastern Ontario Without Breaking the Bank

Bring Your Fam!

Time to Unwind: 6 Spa Havens to Discover In The Seven

5 Amazing Places to SUP in Northeastern Ontario

5 Amazing Bike Rides to Discover

Northern Lights in Northeastern Ontario

Northeastern Ontario's Best Pride Festivals

Fish for one of the World's Rarest Species of Trout

An Insider's Guide to Manitoulin Island

6 Small-Town Gems to Explore in Northeastern Ontario

11 Best Things to Do in Kapuskasing, Ontario