Crossing The Northern Divide

Driving along in Northeastern Ontario, you may notice those distinctive green and white signs announcing that the water flows in different directions. It's a strange thing, though—there’s no water by the signs. There is a moose and a bear silhouette and an elevation number. On one side it says the water flows to the Atlantic Ocean, on the other to the Arctic. What’s that all about?

It’s a line all right, but it's not as neutral as you might think. Historically, these lines have indicated personal and physical boundary lines—some are well demarcated, some are invisible. Sometimes these lines indicate physical features or reflect the social limits of peoples.

A “height of land” is a region of high ground that may act as a watershed boundary. Heights of land were important in the historic fur trade for their influence on the determination of routes and portages and they have affected many transportation routes since then. Drainage boundaries were important to Native peoples in defining territoriality, as they were later to European colonists.

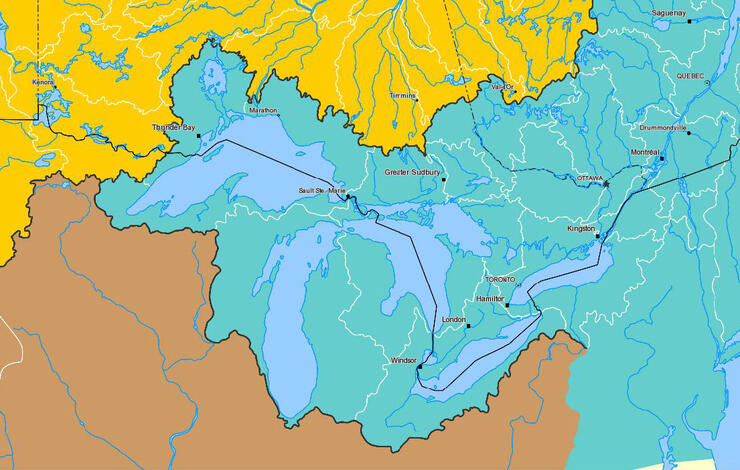

Driving along our northern highways, you will see the signs and plaques identifying the height of land between the Arctic and Great Lakes watersheds. As the northern wilderness came under development, the erratic line of the watershed defined territorial boundaries. The height of land line follows an irregular course of some 2,250 km across Ontario, ranging from 32 to 280 km north of Lakes Huron and Superior.

Gordan Rennie, Regional Issues and Media Advisor at the Ministry of Transportation, Northeastern Region provided some background. The highway signs were installed to complement the installation of Ontario Heritage Plaques near Kenogami, just north of Kirkland Lake. On August 20, 1969, a provincial historical plaque marking the Arctic Watershed was unveiled beside Highway 11 in the District of Timiskaming. This was one in a series of plaques erected throughout the province by the Historic Sites Board of Ontario, which were more recently replaced with a revised bilingual marker.

Getting Physical

The Laurentian Divide—or Northern Divide—divides the direction of water flow in eastern and southern Canada and the northern Midwestern United States. Water north of the height of land flow by rivers to Hudson Bay or directly to the Arctic. Water south of the divide makes its way to the Atlantic Ocean by a variety of streams, including the Great Lakes and Saint Lawrence River to the east, and the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico to the south.

Larry Dyke is a Professor Emeritus from Queen’s University, Department of Geology and has retired to the Talon Lake area. He explained that the most rugged and fragmented surfaces occur in a band extending from the north shore of Lake Superior, across the Algoma highlands, through the Sudbury region and north of Manitoulin Island. It’s here that we find two of the highest points of elevation in Ontario—Ishpatina Ridge, at an estimated 693 metres above sea level within Evelyn-Smoothwater Provincial Park, and Maple Mountain, which is lower on the list but has the highest vertical rise in the province—351 metres on the landscape. “At a close-up scale, there are so many subtle influences on the shape of those lines, especially in flat country,” he says. “Thinking of the grain in a piece of wood, a slightly different cut may give a very different pattern. A slight bevelling of the landscape will move a drainage boundary kilometers.”

According to Dyke, “Most of the rest of the country is controlled by the Canadian Shield as an overall high area with Hudson Bay as a low spot, still rebounding from the last ice age. What we have today is quite different prior to the most recent glaciers. Much meltwater drainage flowed off into the United States, but as rebound occurred, this flow turned towards Hudson Bay.”

The Line

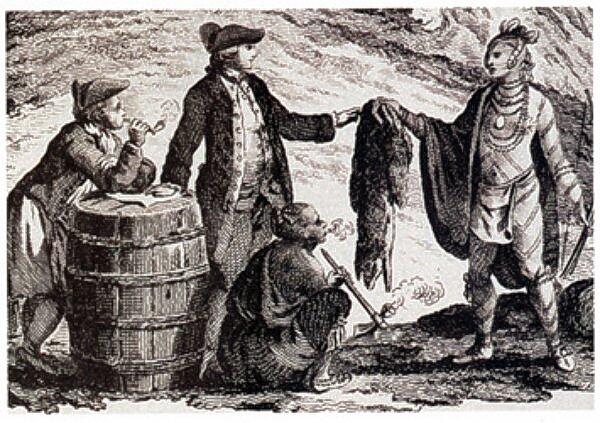

This political line started with the charter granted by King Charles II on May 2, 1670 to "The Governor and Company of Adventurers of England trading into Hudson's Bay," setting forth the sphere of operations of the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC). The HBC was to be the owner of the entire area draining into Hudson Bay.

The land was inhabited by aboriginal peoples, upon whom the Company relied for its supply of beaver pelts. The French soon disputed the HBC's claim to this vast territory, since French missionaries and traders had extended and consolidated Champlain's discoveries into areas that could conceivably be in what the HBC now claimed as its territory. The French all but drove the English out of the Bay in 1696.

The Treaty of Utrecht in 1713 restored sovereignty of the region to Britain, but did not establish any definite limits between the territory of France and that of the HBC. The boundaries were constantly in dispute. Fifty years later, with the signing of the Treaty of Paris, France abandoned mainland North America for good.

The Royal Proclamation of October 7, 1763 set forth the boundaries of the lands acquired from France that year. The continued existence of Rupert's Land was tacitly confirmed, and "any Lands beyond...the sources of any of the Rivers which fall into the Atlantic Ocean from the West and North West" were set aside for their aboriginal inhabitants. What does this mean?

Treaties and Boundaries

This oscillating line then is very important to Canadian history.

In 1986, Nipissing University, Professor Robert J. Surtees of North Bay, in a Treaty Research Report for Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, wrote: “in 1791 the boundaries of Upper Canada were set and the new colony received jurisdiction over the territory west of the Ottawa River between the St. Lawrence River and the Great Lakes waterway and the lands that had been granted to the Hudson Bay Company. Therefore the Upper Canadian boundary was demarcated by the height of land…”

This is significant, for it meant that virtually the entire province was within First Nations territory as defined by the Royal Proclamation of October 7, 1763 which decreed therein were reserved “for the Use of the… Indians as their Hunting Grounds (sic).” In essence further land purchases and treaties were developed to alienate Indian title to the land.

In exchange for this land, the Ojibwe were to receive ₤2,000 at the time, and a perpetual annuity of ₤500; the latter could be increased if the land generated sufficient revenue. In addition, the Ojibwe retained the right to hunt and fish on any of the land by the Crown. The agreement was formalized in what became known as the Robinson-Superior Treaties. The wording of these documents further legitimized the notion that the Arctic Watershed was the southern boundary of the HBC's lands.

The Robinson Treaty for the Lake Superior region, commonly called Robinson-Superior Treaty, was entered into agreement on September 7, 1850, at Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario between Ojibwe Chiefs inhabiting the Northern Shore of Lake Superior from Pigeon River to Batchawana Bay. It is registered as the Crown Treaty Number 60. Under its terms, the Ojibwe surrendered territory extending some 640 km northward to the height of land delimiting the Great Lakes drainage area.

The first Robinson Treaty for the Lake Huron region was signed on September 9, 1850 at Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario between Ojibwe Chiefs inhabiting the Northern Shore of Lake Superior from Batchawana Bay to Sault Ste. Marie and the Ojibwa Chiefs inhabiting the eastern and northern shores of Lake Huron from Sault Ste. Marie to Penetanguishene to the height of land. It is registered as the Crown Treaty Number 61.

The Signs

In Northeastern Ontario there are signs on Highway 11 near Kenogami and Highway 144 near Gogama; also south of Chapleau on Highway 129. In Northwestern Ontario there are signs on Highway 11 near Geraldton; on Highway 17 near Raith, east of Atikokan.

When you're standing on the ground, it is almost impossible to see which way the water is flowing, but the maps make it easier to understand which way the water goes. The direction is related to a set of personal values and physical features, one connected to the other by time and place, a little more complex to comprehend. Stop and take a photo. You don’t need a passport to cross this line. Think about its cultural and physical significance, all within your BIG adventure.

Recommended Articles

The Seven's Best Hikes, Biking Trails and Lakes

7 Best Spots to Check Out in The Seven

Budget Bliss: Explore Northeastern Ontario Without Breaking the Bank

Bring Your Fam!

Time to Unwind: 6 Spa Havens to Discover In The Seven

5 Amazing Places to SUP in Northeastern Ontario

5 Amazing Bike Rides to Discover

Northern Lights in Northeastern Ontario

Northeastern Ontario's Best Pride Festivals

Fish for one of the World's Rarest Species of Trout

An Insider's Guide to Manitoulin Island

6 Small-Town Gems to Explore in Northeastern Ontario

11 Best Things to Do in Kapuskasing, Ontario