Paint it Bright

Ojibway Woodland artist Thomas Sinclair has always loved to draw. “I’ve loved to draw so much and for so long that I don’t remember ever not loving drawing,” he affirms. From Couchiching First Nation, Sinclair grew up in Thunder Bay where he was mentored in the Woodland style by the late Isadore Wadow. “I met Isadore when I was five years old, and he gave me art lessons. He also taught me about the different symbols, where they come from and what they mean.”

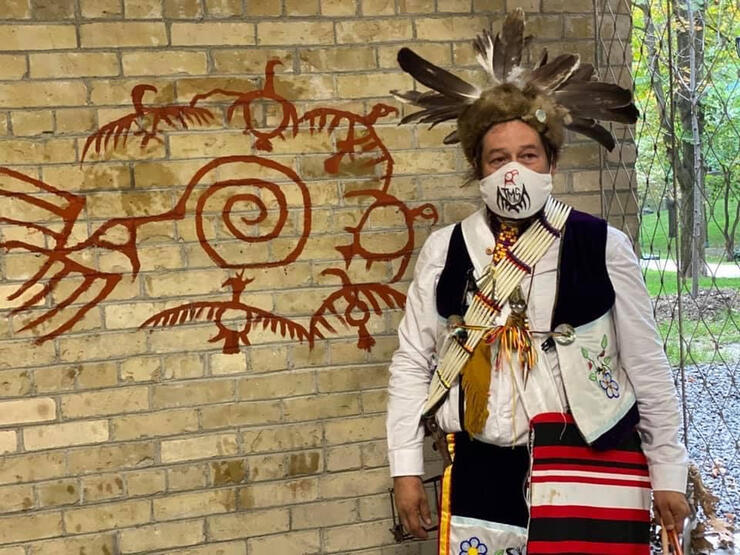

Trained in the Woodland style, Sinclair's interest in art began at a young age.

After Wadow’s tragic death in 1984, Sinclair stopped drawing and painting. For years, he struggled with personal and mental health issues until he reached a very dark place. “My mom got cancer, and my partner had passed away four years earlier. I didn’t feel like I had anything to live for. I was really angry at the world, especially about systemic racism. I’d been screaming about it for decades.”

Seeking healing through art

That’s when, in 2018, he picked up a paint brush again—more than 30 years since he had last done so. He painted a bleak and vulnerable self portrait and posted it to Facebook. “People liked it and started encouraging me to paint. It was the only way for me to get what I was feeling out so I kept painting. I went from that really dark angry place to trying to be at peace and creating images of love and kindness. That’s why I use bright colours; I’m trying to show how grateful I am that I made it through those dark times.”

For Sinclair, much of his artwork has been healing, not only for himself, but for his people. This past October, he took an intensely emotional and spiritual journey to honour the 2,500 year old remains and artifacts of his ancestors, which now rest at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto. He painted a pictograph of seven thunderbirds on an exterior wall of the museum with authentic pictograph paint—he's one of the few artists who still knows how to make such paint. The birds represent the seven clans and form a circle representing a star formation called The Pleiades or the seven sisters. It’s known in Ojibway culture as Bagonageezhik or the hole in the sky. “Because the burial mounds have been dug up, my ancestors have to stay in the museum,” he explains through tears. “It’s really painful, but this was a way to make some peace with it. The thunderbirds show my ancestors the way home through the hole in the sky so we can move forward—hopefully in a more healthy and peaceful way.”

The artist's pictograph, showing his ancestors the way home, on a wall at the ROM.

Now, as a resident of Sault Ste Marie (SSM), Sinclair spends his days painting, inspired by Aadizookaan, the sacred stories told by elders. “I’m nomadic, but this is the place I always come back. With all the pictographs and creation stories here, I feel like SSM is a very important place spiritually and culturally. The longer I stay here, the more I learn about the land and the art in the area. All the Canadian masters have stayed here. To be an artist, I want to be where all the great artists have been.”

An invitation to create a new mural

To capture some of its creative fortitude, the City of SSM aims to develop its arts, culture and heritage sectors through its FutureSSM initiative. To this end, the Summer Moon Festival was launched in June 2020 where Sinclair was invited to be one of the artists to bring large-scale murals to life in downtown SSM. “The project seeks to support reconciliation efforts in our community and celebrate and promote the rich Indigenous arts, culture and heritage unique to our area through public art projects,” says Todd Fleet, Arts & Culture Coordinator for SSM. You can find Sinclair’s mural on Bay Street featuring his signature bright colours with Woodland symbols.

One panel is dedicated to Mishipeshu, one of the most well known pictographs among the Anishinaabe, set in stone by Ojibway spiritual leaders centuries ago. It’s located with hundreds of other images at Agawa Rock, a sacred lakeside site located in Lake Superior Provincial Park.

looking ahead to a bright future

The artist with a selection of his paintings.

Sinclair also plans to participate in the upcoming 2021 Summer Moon Festival this June, creating a new mural and hosting a workshop to discuss the meaning of his artwork. “There will be teachings on what I’m doing and why; what the symbols and colours mean, how they interact and change the tone of the painting,” he says. “I can have the darkest meanest angriest image, but if you paint it bright, you don’t notice that darkness. It’s like giving balance of life—the darkest things can be beautiful in their own way. And the most beautiful things can also be very dark.”

To learn more about Thomas Sinclair, visit his website: https://tmswoodlandart.ca.

Recommended Articles

Ontario Pow Wow Calendar: 2025 Edition

8 Indigenous Tourism Experiences To Book in 2025

Indigenous Restaurants in Ontario

8 Indigenous Experiences to Discover in North Bay

6 Indigenous-owned Accommodations in Ontario

7 Indigenous-Owned Fishing Experiences in Ontario

Pow Wow Road Trip

11 Indigenous-Owned Outdoor Adventure Companies in Ontario

13 Indigenous-Owned Businesses to Visit on National Indigenous People's Day—and Every Day

A Guide to Visiting the Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung Historical Centre

Indigenous Theatre on Manitoulin Island