At one with the water

WATER

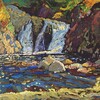

We are freshwater people. People of gaaming and people of ziibi. Water runs through us, around us, and in our homes. Water breaks before we enter the world. The Anishinaabe (original people) have many words for nibi, because it can mean many things to life.

In English, we have one word for water. Freshwater is sacred. It is something worth protecting. When the McGuffins, a charismatic, conservation-oriented canoeing couple, travelled the thousands of kilometres of Lake Superior shoreline, they also carried an important message: Love water. Respect water. Take care of it.

THE GUIDE

I am about to start my own canoe voyage on the outflow for the largest expanse of freshwater on the planet. Fortunately, I have Joanie McGuffin along to help guide our canoe. Not only is she a professional paddler, but she’s an expert interpreter with an impressive bundle of experiences from the land. We get to share special streams of knowledge along this heritage river with our tour group.

Joanie has gathered our group on land at Parks Canada and is explaining how bark canoes were sustainably harvested from the forest. As I hand out skillfully shaped paddles, I catch the pensive looks of participants. Our participants are eager and follow Joanie’s paddling and safety instruction fluidly. I notice Joanie is glowing with enthusiasm as she shares her passion with the group. I can’t decide whether she is energized because she gets to guide our newcomers’ first experience or because it is another beautiful day that she gets to spend on the water. In any case, I am imprinted with Joanie’s positivity as an irrepressible smile spreads to my cheeks. I am not alone—I observe similarly energetic looks spread across our group.

THE PADDLER

I was born and raised in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, along the shores of the St. Marys River. Some of my earliest memories are along this river and many of them are associated with the unknown and fear. That is why I am especially nervous as I carefully shift my weight from the dock along its shores into a canoe. My hand is steadied as a fellow paddler helps me settle into the wooden bench style seat next to hers. I am thankful to not only be guided on this canoe tour, but to get to experience this tour with another 14 paddlers in the same vessel.

The canoe’s hull looks like birch bark, but the rough surface of the uniformly moulded inner belly suggests the canoe is constructed from fibreglass. Joanie describes the 36-foot canoe as “a testament to the traditional craft of the forest”. I only need to grip the grains of wood running along the gunnels and catch my fingers on the twisted spruce root detailing to confirm. I am amazed how these materials held the papery birch bark together, suspending paddlers above the water. I find it fascinating how innovative the people of this area were.

Our guide passes a small portion of tobacco into my hand, and explains why one might offer tobacco to the water. I myself am not an Indigenous person, but I pause to think about what an offering could mean. I pause, my thoughts drift to the sound of the water gently lapping against the canoe. The grounds of tobacco in my hand ground me to the moment as I let out my breath and open my hand, letting go of the tobacco.

Soon enough, we are paddling in rhythm as we coast parallel to an island named after the robust attikamek (whitefish) that once sustained the people who lived and traded here for millennia. I peer over the side of the canoe and my eye meets the shallow sandy bottom. Already we can hear the dull roar of turbulent rapids. At the south end of the island, with a view of the upstream turbulent waters, our guide describes the skillful and agile Anishinaabe fishers; how the stern paddler guided the canoe while standing, and the bow paddler used a dip net to harvest the fish. The canoe has slowly pivoted around to face the city’s waterfront, and I feel the gentle tug of the current pulling us there. The city looks out of place from this view.

We maintain our slow deliberate rhythm. The canoe maneuvers easily with all participants simultaneously pulling their paddles through the water, as our guide’s interpretation of this place eddy in my mind. What would this river sound like in the past? Would the world be silent to the hustle and bustle of an industrious town? Would the roar of the rapids buffer out other sounds? Where would our eyes land on the horizon without the international bridge arcing over the river?

Our guide points out a bald eagle gliding across the sky, pinpointing its next meal. As I inhale the cool, near palpable air, I recognize the faint fresh smell of the outdoors, of the thriving aquatic life, or water itself. Can water have a smell? The diving ducks and the people fishing off the boardwalk all affirm that the river’s fish population is healthy. The elderly paddler in front of me relays to our guide that a public beach used to exist here, in this location, along the waterfront. I envision the clashing of development and industry with nature and recreation. This philosophical argument smoothed out in resistance to the largest lake in the world constantly pouring through the town.

We arrive at the Canadian Heritage Bushplane Centre to conclude our tour. Inside, I test a flake of smoked whitefish and listen as our guide speaks to Chief Shingwauk’s now 200-year-old vision of preserving an environment here, along the river, in which Indigenous cultural values and organizational structures could survive and coexist, or even harmonize, with western values and organizational structures. I consider that our local heritage and culture is like the water of the river that I have been absent to. It flows past us, through us, in us, rarely garnering our real recognition of it being there. I think Chief Shingwauk saw the water.

There are few things more symbolic of the Great Lakes region than the canoe. The canoe has glided across water earlier in the past than the wheel has rolled on land. It has been used for millennia to ply the rivers and lakes of Canada. Just under one-tenth of Canada’s area is occupied by freshwater. The Great Lakes combined comprise over one fifth of the surface freshwater on the planet, making the canoe a natural fit here.

The Lake Superior Watershed Conservancy (LSWC) is committed to protecting Lake Superior. The LSWC is going back to our roots and harnessing the steadfast connection between ecology and heritage that resides within the canoe. The above description is a representation of the tours the LSWC will host in from May to October on the St. Marys River, as well as Gros Cap and Batchawana Bay. Tours are designed to be educational and promote environmental stewardship, while offering participants an intimate perspective from the water.

All of LSWC’s tours are day trips and most are only a few hours long. For longer trips, more advanced paddling, and a scaled outdoor adventure on Lake Superior, I recommend Naturally Superior Adventures. Trips in their Voyageur canoe fill up quickly and are themed to match a variety of interests.

Recommended Articles

9 Facts to Know about the Agawa Canyon Tour Train

A Guide to the Best Urban Fishing in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario

Where to Eat, Dine, and Play on the Sault Ste. Marie Waterfront

Cruising to the Next Level

Canada's Only Bushplane Museum is a Must For Your Bucket List

Why the Fall Is a Great Time to Visit Sault Ste. Marie

Canoe & Kayak Sault Ste. Marie

Peace Restaurant