Life on the lakes

There's something wonderful about the particular silence which blankets the lakes 200 km west of Thunder Bay. In reality, it's not total silence, but one interrupted by the low call of a loon—or in my case, the loon impersonation performed by my hosts, Michelle and Dale, founders of the Voyageur Wilderness Programme. Michelle tells me it's one of her favorite birds. "It's because of its majestic calls and its ability to dive deep into the water—up to 60 metres deep," she reveals.

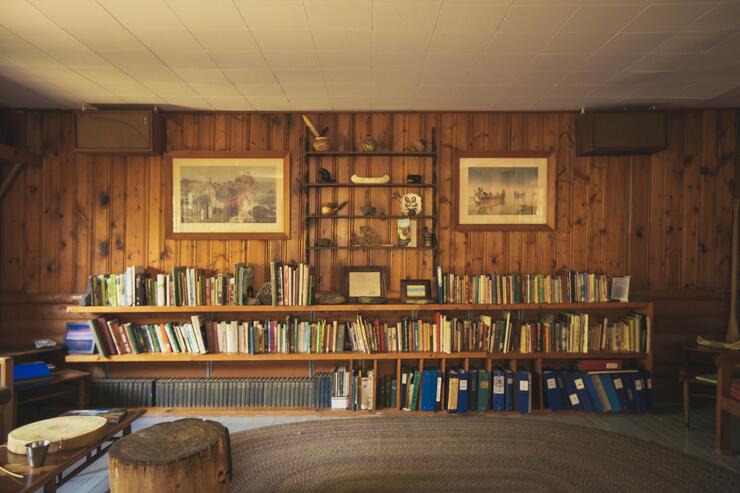

Their home—and mine, for a short while—is Voyageur Island, a low, grassy chunk of land rising above the mirror-like water of Nym Lake, on the border of Quetico Provincial Park. Michelle, like her parents who ran the business before her, and now live nearby, is Métis: a descendent of both the first European settlers to come to this part of the world, and Canadian First Nations. In the beautiful log cabin which serves as the island's dining room, library and meeting room, the walls heave with items providing an insight into her Métis ancestry.

There's a photo of her father wearing the ceinture fléchée, the colorful, wide waistband regarded as part of the Métis national dress. There are beautiful paintings depicting the voyageurs (fur trade employees) who opened up this remote part of Northern Ontario hundreds of years ago, paddling for weeks on end in fur-laden wooden canoes which they slept under at night.

Today, people come from all over the world to Nym Lake. They rent one of Michelle and Dale's canoes and head off into the wilderness for weeks on end, using the portages (trails of varying lengths) to hop from one lake to another, and camping on deserted beaches. Or they'll sign up for shorter forays into the park, returning to Voyageur Island when dusk falls to eat homemade meals by the campfire before bedding down in the cosy bunkhouse or in one of the island's cabins.

When I'd arrived at the lakeside pick-up point to see Michelle chugging across the water towards me, I'd been driving for more than an hour but hadn't seen a single person. On Voyageur Island, my home from home is one of the pine-fragranced log cabins—there are six in total. I'm admittedly somewhat nervous the first time I walk the short distance from the main lodge to my cabin, constantly looking over my shoulder at the slightest rustle, recalling how one of Michelle's first stories related to the time a young bear swam over to the island and clambered up a tree before disappearing back the way it came.

A blustery wind is whipping up foam-topped waves and Michelle decides it's best to opt for a motorized tour of the lake rather than a canoe-based one, and I'm secretly grateful—the last time I was in a canoe was in Tobago, when my excursion involved a short paddle across a glass-flat lagoon. We speed across the water. Occasionally I spot a lone cabin on one of the islands we pass. Michelle explains that few people live inside the park, and it's no longer possible to buy plots of land. Any newcomers have either bought their cabin from a current resident or inherited it.

We stop at a tiny, deserted island and clamber up the bank. An almost perfect circle of bright green grass indicates the location of a recent campfire, fresh growth supercharged by the nutrients from an injection of ash. Michelle tells me about the recent storm she watched glide across the lake towards Nym Island, and talks sadly about a huge tree which was uprooted—adding, however, that it won't go to waste.

It appears few islands escaped unscathed, and before we head back to the boat Michelle notes the position of another fallen giant, explaining that she'll relay its position to park warden Trevor Gibb, who'll come and remove it. She adds that in winter, when the ice is thick enough, they'll often drag nearby fallen trees back across the water to their own island.

When I ask Michelle what she loves most about living out here on the lakes, she struggles to narrow it down, describing the gorgeous sunsets, the heady scent of the boreal forests, the spectacular dance of the Northern Lights in winter, and the sense of being connected to her ancestors through her home on their canoe routes. Although Michelle tells me it's a hard question to answer ("It's like being asked to pick a favorite child!"), my inner journalist isn't satisfied and I press her to narrow it down. "I'd choose the traditional historical Quetico canoe routes, with their pictographs, rivers and lakes, and rock formations," she decides.

Her top tips for visitors to the park? "Plan ahead and be prepared, and use the expertise of an outfitter. Ensure your vision meets reality by making a realistic trip route. And engage in eco-friendly practices—leave no trace." As for the essential items? Michelle suggests opting for a headlight over a flashlight so that hands are kept free, along with carabiner clips—a multipurpose miracle product which can be used to secure various items and hang up clothes. And dry bags are an essential when it comes to protecting sleeping bags, in the event of an accidental dunking.

It's all wonderfully wild. I live in a small town in one of the leafiest areas of southern England. When I go for my daily bike ride I spot squirrels, herons and shrews, and I regularly catch the beady eyes of a fox in the headlight of my torch. But I'm well aware that the creatures here are much larger: bears, moose, cougars and coyotes. This is pure unadulterated wilderness.

Recommended Articles

Epic Lake Superior Adventures Near Thunder Bay

Experience Your Perfect Summer in Thunder Bay

Eco-Friendly Travel in Thunder Bay

Wellness Retreats in Thunder Bay

LGBTQIA+ Friendly Businesses in Thunder Bay

Uncovering Thunder Bay's Hidden Gems

Top 10 Interesting Facts About Thunder Bay

Work Hard, Reward Yourself: Discover Thunder Bay’s Best Winter Experiences

Thunder Bay Winter Fun Guide 2025

12 Best Places to Stay in Thunder Bay

5 Fantastic Ways to Explore the Water in Thunder Bay

5 Reasons to Bring a Conference or Meeting to Thunder Bay, Ontario

21 Ways to Enjoy Thunder Bay

The Remembrance Poppy and its Thunder Bay Roots

Why You Should Always Travel With Fishing Gear in Thunder Bay

This new cruise ship sails into Thunder Bay

Chill Out in Thunder Bay: Why Cold Plunges Are Hot Right Now

Walk This Way: Self-Guided Art and History Tours in Thunder Bay