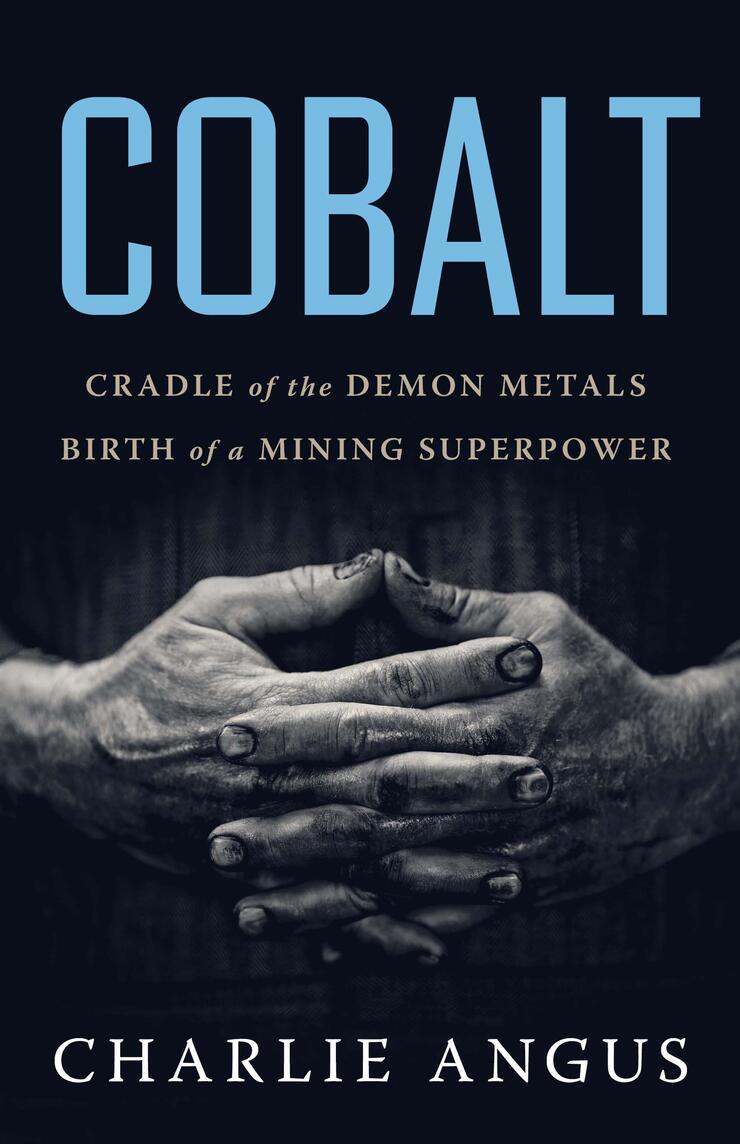

Discover the Hidden History of Cobalt, Ontario

Editor's Note: Cobalt, Ontario is known (by geologists at least) as one of the world's most famous mining towns. The historic spot a few hours north of Toronto sprang into existence almost overnight after a massive deposit of silver was discovered at the turn of the century. Prospectors flocked in the thousands to this patch of Northeastern Ontario wilderness to get rich. And get rich they did. What followed was one of the most interesting tales in Canadian history—much of it lost to memory. Until now. We caught up with the author of this new investigation into the world's one-time mining superpower to ask him a few questions.

Charlie Angus has been the Member of Parliament for Timmins-James Bay since 2004. He is the author of eight books about the North, Indigenous issues, and mining culture, including the award-winning Children of the Broken Treaty. He is also the lead singer of the Juno-nominated alt-country band Grievous Angels. Charlie and his wife, author Brit Griffin, raised their three daughters at an abandoned mine site in Cobalt, Ontario, that looks like a Crusader castle. Cobalt: Cradle of the Demon Metals, Birth of a Mining Superpower is his latest book.

Who is the book Cobalt for?

I wrote this book for people who may not have any idea of where Cobalt is, or any connection to stories in Northern Ontario.

We have this tendency in Canada to treat our stories as local, but in my book, I argue that the story of Cobalt has implications for the history of all of the Americas. In that way it’s a global story because mining and the movement of capital affect us globally.

I noticed that Cobalt is invested in portraying the diversity of people in the mining town. Tell me a little bit about that.

Some of the stories we tell ourselves in Canada go along the lines that we are a tolerant and multicultural place. Toronto and Vancouver have given us this image of the tolerant and multicultural Canada, but this coming together of diverse people actually begins in mining towns. If you were an immigrant family in the early 20th century you went to the frontier. When my family came to this region as immigrants it was understood they would go with all the other immigrant families. This kind of coming together created tensions as well, certain conflict, but it also helped to build a very distinct identity of place. Families grew up together. In my book I focus on the Syrian community—I could have focused on any number of communities but the Syrian community was in northern Ontario from the beginning yet we don’t seem to know that as historical knowledge in Canada.

What I try and challenge in the book is that history in Canada has been told from the dominant settler perspective which is Anglo-Saxon and white. Yet there were much more multi cultural, multi racial towns that were built on Indigenous lands. When we start to put those stories in, we get a much more complex, I think a much more fascinating story. This more complex picture of Canada has a lot to teach us than an airbrushed history we may have been taught about Canada before.

There’s also something about mining boom towns that is so fascinating—because people who go there begin to act as characters. And they’re acting in ways they couldn’t act back in their home countries. They get to reinvent themselves. So, there’s a larger-than-life joy of living, even amongst the tragedy and the conflict. That’s why I spent a lot of time writing about the vaudeville theatres in the book. To me it is fascinating that in a town that is under continual crisis and people are working really hard—yet they run six to seven live theatres every week. And, they have two professional hockey teams!

In the case of Cobalt, because mining companies are so mercenary about extracting everything without putting much back in, you had this place that looked like a shanty shack town—but it also had connections to New York. There was no proper fire department but there was live theatre and gambling. The dichotomy to me is what is engaging [as a subject], and of course tragic.

You’ve written several books about Canadian topics. What inspired you to write about your hometown?

This is my eighth book. The theme I write about in all my books is place and memory. And why history in Canada doesn’t reflect what really happened. I am really fascinated by what people remember and what they choose to forget. I was born in Timmins, the porcupine region—and I did a book about that. Looking at some of the darker and wilder stories there but with less analysis than I have here. The first book I wrote was with my wife Britt Griffin and it was a book about Cobalt. We had just moved there and we loved the mythology. Cobalt has a rich mythology—a rich oral history and we fell in love with it, and with the stories. I then understood there was a more complex story about Cobalt which hadn’t been told.

I have been thinking about this book for a long time. I live in a family with strong women who have strong opinions and we have talked about some of these ideas over and over again. I worked on this book for a number of years. The process of putting this book together was like detective work. Initially I knew there was a broader story but I did not know if I would be able to find it. For example, many of the immigrant families living in the area were not covered in the newspapers [of the day]. The dominant white class in Canada was covered. Women from this dominant class may have had time to write dairies [that we could later refer to] but the Syrian women did not have time to write diaries. They were working maybe 12 hour days. I didn’t have all of those voices to balance out the narrative.

Finding out the history of the Black community in the area was something I had been trying to do for years. A friend who was a Black artist had come from the United States to Cobalt, and he said to me where is the Black history of Cobalt? He said, ‘Wherever there’s a frontier there’s a Black history.’

When I was much younger, I was invited to meet Bob Carlin. It was a chance meeting with him thirty years ago. When Carlin found out I was from Cobalt, he talked about Jim McGuire and the Western Federation of Miners. After the chance meeting, I knew where to look. I could start to piece together a complex history.

Could you talk about the editorial process which led to the published edition we see in bookstores today?

With the editors, we worked back and forth a lot. I will say a big influence on the book is Bruce Walsh, the former publisher of House of Anansi Press. The book, Clearing the Plains was a huge influence on me.

With Cobalt, Bruce said to me, ‘you need to make this book about today.’ To tie in connections to international struggles and the global market, and to talk about Canada today and its role as a mining superpower. I had written the book, and then the structure of the book was adapted to address pressing issues of today. That’s why people are moved by the book. It is a book about history but one that shows us how we got to this point and decisions about where we are going to go from here.

Author Charlie Angus

Recommended Articles

Northern Ontario’s Most Unique Stays

U-Pick Berries and Fruit in Northern Ontario

The Best Ice Cream in Northern Ontario: Where to Go This Summer

Fueling the Adventure: A Sweet Butter Tart Road Trip Through Northern Ontario

Top 10 Things To Do in Northern Ontario

See the Leaves Change: Fall Colour Report Ontario 2025

7 Amazing Northern Ontario Islands You Must Visit

The Agawa Rock Pictographs

6 Dark Sky Preserves in Ontario

Best Vinyl Record Stores Ontario (That aren't in the GTA)

The World's Smallest Record Store Is Not Where You'd Expect

The Northern Ontario Beer Trail: 8 Essential Stops For Beer Lovers

12 Times TikTok Was So Northern Ontario

7 Species Worth Fishing for in Ontario

10 Sights To See By Motorcycle In Northern Ontario

A Road Trip to Red Lake

The Eagle

Pride Events in Northern Ontario 2025

How to Book a Campsite in Ontario

9 Films About Northern Ontario You Have To Watch

7 Stompin’ Tom Connors Songs About Northern Ontario

17 Amazing (and Random) Vintage Ontario Tourism Ads That Will Definitely Make You Want to Travel This Summer