Experience Spirit Island

When the Great Spirit created Manitoulin Island, it was so beautiful He called it home. He then placed the Odawa people here and so the Odawa call this island Odawa Mnis, Island of the Odawa. The Ojibwe, however, called it Mnidoo Mnis or Spirit Island. That spirit is palpable as the leading edge of your motorcycle approaches the largest freshwater island in the world.

Most of Manitoulin’s secondary roads have a tar and chip surface. Generally it’s in good shape but if they’re resurfacing, you want to know before heading out. Don’t be caught off guard as I was. Use the Go Tour Ontario trip planner to check for road construction.

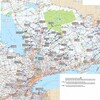

Situated in Lake Huron, Manitoulin is the largest freshwater island in the world. Access is either via Chi Cheemaun Ferry to South Baymouth, or the one-lane swing bridge at Little Current in the north, where the stoplight that controls traffic is the only one on the island. Small communities are connected by roads that consistently deliver scenic views as they change elevation and weave between waterways.

For millennia, Odawa people called Manitoulin home, joined much later by Ojibwes and most recently by Pottawatami people. Collectively, they form the Three Fires Confederacy and are known as Anishinaabeg—the people.

Anishinaabe Cultural Historian Alan Corbiere, is well-versed in the history and legends of the land. He shared a story of Nanabush, a legendary being who was sent to teach people how to live. Nanabush was a big tease, something that regularly got him into trouble. One time he was being pursued from Tobermory with his grandmother in his canoe. Landing at Providence Bay, he ditched the canoe, hoisted his grandmother on his back and took off across country. The burden became too much so he threw her in the lake, promising to come back. You can still discern her shape as Old Woman Island (Treasure Island) in Mindemoya Lake.

Nanabush kept running to M’Chigeeng (West Bay) where he thought he’d get caught, but instead decided to take a stand and dropped his spear. As you head south over the hill at Honora, you’ll see two bluffs of different elevations—Nanabush’s barbed spear head and spear handle are the lower and upper bluffs respectively. Non-Native people call this place Cup and Saucer.

Stop by the Ojibwe Cultural Foundation (OCF) in M’Chigeeng to take in the museum, art gallery, healing lodge, elder's room, and with luck, dancing.

The Rolling Thunder Dance Troupe presented by the Great Spirit Circle Trail, put on an extraordinary performance, with each dancer garbed in regalia reflective of their personal story. Inspired by visionary Mary Lou Fox, Steven’s mother, it was founded in 1974 to preserve and revitalize the heritage of the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Pottawatomi people. Just around the corner, Lillian’s Crafts offers not only traditional pieces by local artists, but they’re liberal in sharing local lore.

Esther Osche is the Lands Manager for the Atikameksheng Anishnawbek (Whitefish Lake First Nation), Community Historian and Traditional Storyteller. She also rides a 1992 Springer Softtail. I was honoured to join her around the campfire at as she relayed the Legend of Dreamer’s Rock to a group of community children, in the same manner it’s been passed down to her through the grandparents.

Esther feels a strong connection to her ancestors and tribal identity as she rides. An intimate knowledge of the waterways, travel routes, and portages lives in her DNA. “They were constantly in motion and I feel good because I’m in motion,” she says. “I love the mountains because they’re where they went for their vision quests. I think about how they travelled, inside and out, and the thrill of going some place—throwing all the supplies into the canoe and on to the next camp because now we’re going to fish. And moving back to summer grounds where everyone would gather to meet and celebrate. Then as the winds and seasons change, settling down for the winter.”

She relates to other First Nations as she rides through their territory because she knows their history and how they settled there. “When something happens at that community, like a big gathering, preservation teaching, or special celebration, we go if we can,” she relates. “It’s a lot like how we may have lived long ago.”

Wikwemikong First Nation on the eastern peninsula is Manitoulin’s largest Anishinaabe community and Canada's only officially recognized Unceded Indian Reserve. The road in is a motorcyclist’s dream, taking you to people who are welcoming to visitors and eager to share their culture and history.

Wikwemikong Tourism has a wealth of resources on local points of interest and events, including the historic ruins of the Jesuit Mission. A highlight of the summer, the Wikwemikong Cultural Festival is held every Civic Holiday weekend. For the past eight years acclaimed Canadian Country Music Artist Crystal Shawanda who grew up here, has kicked it off.

Sitting around a picnic table in Little Current overlooking the water, I listened to the riders Steven had assembled. Duncan Pheasant, artist and municipal worker whose art is featured at the OCF, Godfrey Shawanda, traditional healer and brother to musician Crystal, and Robbie Shawana, a councillor at Wikwemikong described their spiritual connection to movement, the land, and its history. They invite non-natives to come to Manitoulin and get off the beaten path, stop in the communities and talk to people, and ask questions. Enjoy the festivals. They’re a great way to learn the culture.

Esther Osche encapsulates the message well. “Don’t just ride by. Stop. Repose. Watch a sunset over a beautiful place like Elizabeth Bay or in the La Cloche Mountains. Don’t rob yourself of that.”

Welcome to Manitoulin.

Additional Resources:

Note: Spelling of terms, such as Anishinaabeg, Ojibwe, mythological characters like Nanabush and places like Mnidoo Minising vary between publications. It’s because they were translated phonetically from Ojibwe into English, sometimes via French.

Special gratitude goes to Steven Fox-Radulovich who shared his knowledge and acted as a facilitator to make this experience possible.

Recommended Articles

Bucket List Motorcycling in Ontario, Canada 2026

Ontario's Best Twisties: Five Roads to Get Your Lean On

The Big Belly Tour—A Complete List of Ontario's BBQ Joints

It's Bike Night in Ontario 2024

Ontario's Top Twisties

Have You Ridden Canada's OG Highway? Here's Why Every Rider Needs to Hit Up Historic Highway 2

23 Amazing Photos That Prove PD13 Is Still The Best Motorcycle Event Ever

Motorcycle Swap Meets in Ontario—The Complete List for 2025

And a Vespa shall lead them all...