There's Alpacas! And you need to visit them!

The alpacas are humming. We’ve just arrived at Alpaca Valley Farm in the Slate River Valley south of Thunder Bay, and co-owner Darryl Wilson is getting their feed ready—pellets mixed in with oats, barley and corn. Humming, apparently, is how these tall fuzzy dudes communicate, and this particular hum means they’re happy to see their midafternoon meal. And while the alpacas are equipped with their thick fur coats for this bone-chilling winter day, we humans are a little chilly, so we all head inside to the well-kept barn for feeding time.

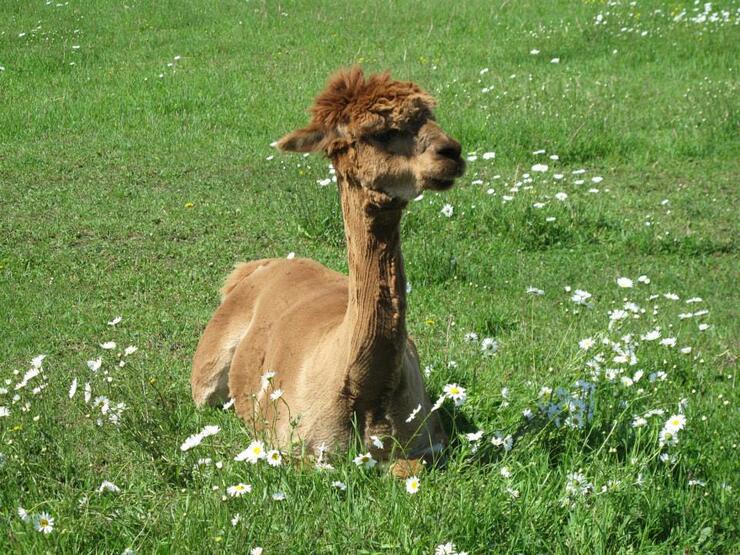

First though, Connie Wilson, the other half of this husband-and-wife team, introduces us. Escobar, the oldest at age 17, is the chestnut brown alpha male and the boss, who gets to eat first and picks where to poop in the field. There’s the reddish-brown El Bandito, so called because he has moustache-like black markings on his white muzzle. Presley and Monsanto are cream-coloured fuzzballs, and are a little harder to tell apart, but Presley has a bit more of a pompadour going on, naturally. These males are pretty darn irresistible, with naturally mellow dispositions, big brown eyes fringed with loooooong eyelashes, sweet expressions and soft curly hair that feels good to pet.

After Escobar gets his fill, Connie puts him on a lead and brings him out into an open area of the barn, while the rest eat their meal in their pen. He stands quietly beside Connie and our group—two adults, and three kids between five and seven—take turns snapping selfies, stroking their necks and backs and even getting a whispery kiss on the cheek. We’re smitten.

The Wilsons bought their alpacas in Manitoba about 10 years ago and built a small, bright red barn at their 40-acre rural property on Highway 130, which has beautiful views of the Nor’wester Mountains. Connie is a retired nurse and Darryl is a semi-retired police officer, and while they didn’t have much farm experience outside of Darryl owning a horse as a teenager, they knew they wanted a little farm business of some kind, and gentle alpacas suited them. Connie explains that these alpacas are the huacaya breed (the other kind of alpaca is called suri, and they have more dreadlock-like-type fur).

In warmer weather, Escobar & Co. spend their days grazing and hanging out in the two-acre fenced-in green field. “We shear them in May,” says Darryl. “That gives them time to grow it back by fall so they can stay warm.” Each alpaca produces about eight pounds of fleece (two garbage bags full!) a year, which is then spun into warm, soft yarn at an Alberta mill. How does it compare to sheep’s wool? Alpaca fleece and yarn won’t mat or pill, doesn’t contain lanolin, which some people react to. The core of the fibre is hollow, which means it holds heat better than wool—some reports say it is up to eight times warmer than wool. And as many of already us already ruinously know, it’s super-soft.

About four years ago, Connie and Darryl, both friendly, soft-spoken people who patiently answer all our many questions, decided to open the farm to the public and establish a farm store. So, after one last snuggle with the alpacas we step into the warm, welcoming shop space that’s attached to the barn. You can buy yarn made from fleece from Escobar, Presley, El Bandito and Monsanto to knit up your own socks or sweaters, or made-in-Ontario alpaca socks (I, of course, buy both). Other goodies include slippers, original alpaca artwork, boot insoles and pre-printed alpaca painting canvases. The shop features nice country touches like barnboard, a working antique telephone and a pump organ, and Peruvian photos and souvenirs from the Wilson’s recent trip to Peru see alpacas on their home turf.

To visit the alpacas, just contact Connie and Darryl via the Alpaca Valley Farm Facebook page to set up a time. We, too, were humming with happiness after our visit.

Recommended Articles

12 Best Places to Stay in Thunder Bay

5 Fantastic Ways to Explore the Water in Thunder Bay

Thunder Bay Winter Fun Guide 2025

Uncovering Thunder Bay's Hidden Gems

5 Reasons to Bring a Conference or Meeting to Thunder Bay, Ontario

21 Ways to Enjoy Thunder Bay

The Remembrance Poppy and its Thunder Bay Roots

Why You Should Always Travel With Fishing Gear in Thunder Bay

This new cruise ship sails into Thunder Bay

Chill Out in Thunder Bay: Why Cold Plunges Are Hot Right Now

Experience Your Perfect Summer in Thunder Bay

Top 10 Interesting Facts About Thunder Bay

Walk This Way: Self-Guided Art and History Tours in Thunder Bay