Murdered Midas: The True Crime Story of the Kirkland Lake Millionaire

Before I started researching the mining history of Northeastern Ontario, I had never been further north in the province than Sudbury. In my road atlas, the drive from Ottawa to Kirkland Lake did not look too intimidating, and I had scheduled my trip in the narrow window between ice-out and blackfly season. I traced the line on my map that threaded its way towards Iroquois Falls, circumventing endless lakes and running past small town the names of which pulsate with history—Cobalt, Haileybury, Englehart, Swastika. My destination was Kirkland Lake, a town that once boasted the richest mine that Canada has ever known.

My first mistake was that I didn’t realize that the scale on my map dramatically changed when I hit North Bay, trebling the distance that one centimeter represented. My second mistake was to assume that I would be driving through the relentless tangle of thick bush, interspersed with the rocky outcrops of Canadian Shield. That was how it began as I drove through the Temagami region. But then I crested a hill and saw before me an arable landscape more typical of Southern Ontario, with big farms and grain silos. This was the Clay Belt. And the Clay Belt was one of the reasons that the great Ontario Gold Rush of the early twentieth century got going in the first place.

Old-timers in Ontario’s North grit their teeth when people extol the romance and excitement of the 1890s Yukon Gold Rush. The stampede to Canada’s distant subarctic region has been immortalized by writers like Jack London and Pierre Berton. But in terms of productivity, the Yukon was a blip compared to Ontario’s Gold Rush a few years later. The gold mines that developed in and around Kirkland Lake, Porcupine Lake, Timmins and Little Long Lac produced ten times as much gold as the Klondike field, and would make Toronto a global mining centre.

The gold rush was triggered by the construction of the Temiskaming & Northern Ontario Railway—the old T&NO. The provincial government laid the tracks north in the hope of attracting settlers to the Clay Belt. But as the track-layers tore away the undergrowth, they caught sight of the dull gleam of precious metals in the newly-exposed rocks. Soon it was flannel-shirted prospectors and silver-tongued promoters, not settlers, who crowded into T&NO carriages.

The first big find was at a clearing where veins of silver lay close to the surface. By 1905, there were 16 mines operating in the raucous mining camp called Cobalt, which boasted a population of several thousand. Between 1904 and 1920, Cobalt mines supplied 90% of Canada’s silver production.

The railroad tracks crept north, and when they reached 366 kilometres north of North Bay, there was a massive gold strike at nearby Porcupine Lake. And a man on the other side of the continent—an American who had already spent fifteen years looking for gold all over the globe—started paying attention. Harry Oakes, a tough and single-minded 37-year old with few friends and a brusque temperament, headed north, towards another barely-surveyed patch of water called Kirkland Lake.

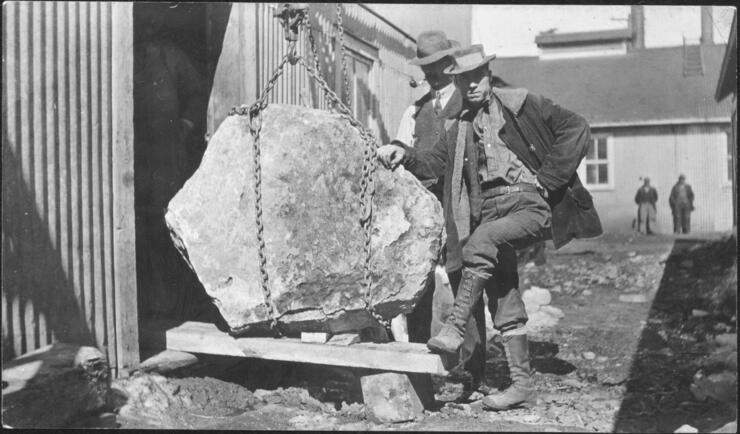

The tale of how Harry Oakes staked his claim on a bitter night in January 1912 is a legend in the North, I discovered. So is the story of how Oakes managed to keep control of his gold mine, unlike all the other prospectors who, lacking the means to develop their claims, sold out to promoters and mining companies.

I spent a happy week in Kirkland Lake doing my research. The first highlight was Toburn Mine, once known as the Tough-Oakes Mine and the first operational gold mine in town. Today, it is the only mine shaft remaining of the six that once dominated KL. A friendly guide (and claim owner) explained the mechanics of hard rock mining and gave me a cylindrical core sample.

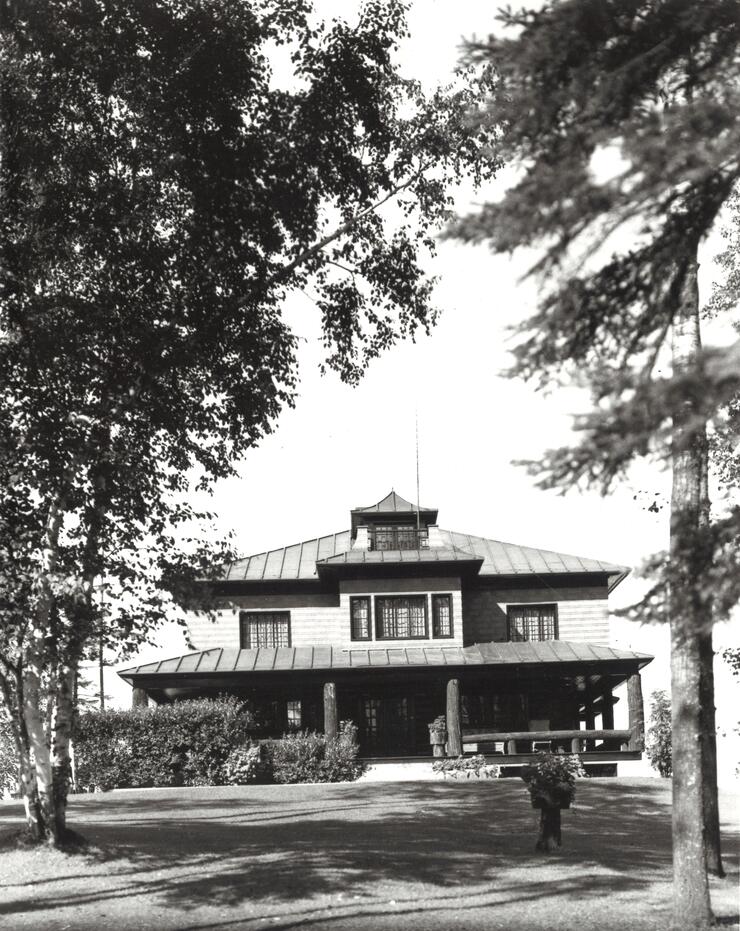

The second highlight was the magnificent mansion known as the Chateau that Harry Oakes built for himself and his family once Lake Shore, his gusher of a mine, went into production. Today it is the Museum of Northern History, where manager Kaitlyn McKay supplied me with fascinating materials about the region’s history and the man who remains a hero in the north.

It would have been happier for Harry Oakes if his legend had ended there. Instead, his name is now linked to a much bigger story, one that crime novelist Erle Stanley Gardner tagged “the trial of the century.” Outraged by Canadian levels of taxation, the multi-millionaire decamped in 1934 to a tax shelter, the island of New Providence in the Bahamas. Nine years later, Harry Oakes was brutally battered to death in Nassau. The chief suspect was acquitted because of police incompetence, and the crime remains unsolved.

Murdered Midas is out now–buy your copy here and find out more about Kirkland Lake's resident gold baron and his mysterious death

Read all about the case in Charlotte Gray's award-winning book, Murdered Midas: The Millionaire, His Gold Mine and a Strange Death on an Island Paradise. Now out in paperback.

Recommended Articles

The Seven's Best Hikes, Biking Trails and Lakes

7 Best Spots to Check Out in The Seven

Budget Bliss: Explore Northeastern Ontario Without Breaking the Bank

Bring Your Fam!

Time to Unwind: 6 Spa Havens to Discover In The Seven

5 Amazing Places to SUP in Northeastern Ontario

5 Amazing Bike Rides to Discover

Northern Lights in Northeastern Ontario

Northeastern Ontario's Best Pride Festivals

Fish for one of the World's Rarest Species of Trout

An Insider's Guide to Manitoulin Island

6 Small-Town Gems to Explore in Northeastern Ontario

11 Best Things to Do in Kapuskasing, Ontario